There are a lot of claims being made about protein in the media and among internet “gurus”.

Are you confused about whether protein will help you build muscle and lose fat? Or will it weaken your bones, damage your kidneys, and cause cancer?

Well, you are not the only one. There is a lot of confusion out there on this topic.

In today’s episode, Ted invited Dr. Stuart Phillips, the premier researcher of protein and its effects on exercise and health, to clear up things for you.

He will talk about why protein is so important to our health, how we lose muscle as we age and how to prevent it, why “exercise is king and nutrition is queen” for health, what “protein fasting” is and whether you should try it and so much more.

He will also reveal the most important type of exercise you can do and how much protein you should eat daily.

Listen now to understand how protein can be the KEY to living longer.

Today’s Guest

Dr. Stuart Phillps

Dr. Stuart Phillps, in addition to being a full Professor in Kinesiology, is also an Adjunct Professor in the School of Medicine at McMaster University. He is a fellow of the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) and the American College of Nutrition (ACN). His research is focused on the impact of nutrition and exercise on human skeletal muscle protein turnover. He is also keenly interested in diet and exercise-induced changes in body composition.

Connect to Dr. Stuart Phillps

You’ll learn:

- How a broken leg led Dr. Phillips to study protein in the lab

- What you should do if you’re confused about mainstream nutrition advice

- Why protein is so important to your health

- How we lose muscle as we age and how to STOP it

- What age your body starts losing muscle if you’re not active enough

- Biological age VS chronological age

- What “sarcopenic obesity” is (and how to know whether you have it)

- Why “exercise is king and nutrition is queen” for health

- Why something is always better than nothing when it comes to exercise

- This is the most important type of exercise that you can do

- Why being in great shape beyond your 40s and 50s requires a plan

- What you should know about the connection between protein and cancer

- What “protein fasting” is and whether you should try it

- Does a high protein intake cause kidney damage?

- Is a high-protein diet bad for your bones?

- How much protein should you eat every day?

- What time of the day is it important to eat protein?

- What you need to know about vegan and vegetarian protein sources

- And much more…

Related Episodes:

Links Mentioned:

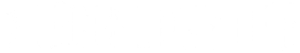

Do You Need Help Creating A Lean Energetic Body And Still Enjoy Life?

We help successful entrepreneurs, executives, and other high-performers burn fat, transform their bodies, and grow successful businesses while enjoying their social life, vacations, and lifestyle.

If you’re ready to have the body you deserve, look and feel younger, and say goodbye to time-consuming workouts and crazy diets, we can help you.

Go to legendarylifeprogram.com/free to watch my FREEE Body Breakthrough Masterclass.

Podcast Transcription: Facts & Myths About Protein For Health And Longevity with Dr. Stuart Phillips, Ph.D.

Dr. Stuart Phillips: We need to set the record straight on this, and it’s the clearest example of what I call flawed circular logic. And so somebody who has kidney disease, their beginning a pathway to what we call kidney failure, they’re put on a low protein diet and what we do know about people who are on that, they live a little bit longer. Fair enough, you know, the kidney is beginning to fail, so it doesn’t want to filter substances that are due to protein and lots of other things.

But the bottom line is, that’s the observation. So then a lot of people say, “Uh-huh, well, this person who has kidney failure is on a low protein diet, they live longer. Therefore, it was protein that causes kidney failure.” And I’m like, “No, that’s not true. You can’t say that, unless there’s some data showing that higher protein, at least maybe is associated with kidney failure, and the amount of data that shows that is next to nothing.”

Ted Ryce: You were just listening to Dr. Stuart Phillips, what’s up, my friend? And welcome back to another episode of the Legendary Life podcast. I’m your host, celebrity trainer, and high-performance health coach, Ted Ryce. This is a podcast for men and women who are looking to boost their energy and upgrade their health. So get ready to learn proven health, fitness, and mindset strategies to unlock your full potential.

And today, it’s going to be all about clearing up your confusion about protein. We hear so many people claim so many things about protein. For example, if you’re in the bodybuilding space, you’ve got to eat protein to build muscle, you’ve got to eat protein to lose fat, because of its high thermic effect of feeding, and you’ve got to make sure you get enough protein, right?

And then there’s the other side where people are claiming oh, well, protein will damage your bones because it makes you acidic. Protein can be damaging to your kidneys, and can even possibly be pro-cancer, it can cause cancer, because of the influence it has on something called mTOR.

So today, I thought well, why don’t we clear that stuff up? And who better to ask then the premier researcher of protein and its effects on exercise and health than Dr. Stuart Phillips? And if you don’t know Dr. Stuart Phillips, you’re in for a real treat. Because this is, like I said, the guy who is the most knowledgeable person, the guy doing the research.

So a lot of the things that you read in the media are based on what guys like Dr. Stuart Phillips does in his lab, and he’s going to clear up so much for us today, you’re going to learn the truth, and what is important for you what you can take away from what Dr. Stuart Phillips has learned from his studies in his lab. And you’re going to learn so much it’s going to help clear things up for you.

Dr. Stuart Phillips, welcome to the Legendary Life podcast.

Dr. Stuart Phillips: It’s my pleasure to be here, Ted, thanks for having me.

Ted Ryce: I’m so excited to have you because we’re going to be going into your expertise, which is protein. And protein’s extremely hot right now. I had a friend of mine who does some consulting work for food corporations, and a lot of them are busy trying to build protein products because they know demand for protein foods, it’s rising.

On the other hand, we have a lot of people who are a little bit concerned with protein with documentaries, like What The Health, where we’re saying, well, protein, especially animal based sources of protein, raise your risk for getting cancer, and a lot of people are left confused about okay, well, why is protein important? How much do I need? And does it really cause cancer or eat my bones? So you’re going to help us clear that stuff up today?

Dr. Stuart Phillips: I’ll do my best.

Ted Ryce: Absolutely. And before we get rolling, I think it would be kind of cool for people… I know you always get asked, “Hey, what do you do? Tell the listeners a little bit about yourself.” But I think it’s really important because you were an athlete and you study biochemistry, but now you do something kind of totally different in the nutrition and kinesiology realm.

Dr. Stuart Phillips: Yeah. So I think the best way is to sort of tell the story as an undergraduate student, I probably would have taken kinesiology or exercise science hadn’t existed. But it was physical education at my school, which I was interested in, but not as interested, I really enjoyed the science, to be honest with you. So I chose biochemistry as my undergraduate. It really wasn’t until my last year of university that almost by a freak accident, I actually broke my leg playing rugby.

I didn’t have rugby to play, and then all of a sudden, I found myself in the lab, and realized that I really enjoyed doing science and conducting experiments. And really, the blend of what I really enjoyed doing because I was always active. I was, as I said, a varsity rugby player, love to, you know, everything I ever did in the gym was to be better as an athlete, to blend the two.

And that’s what kinesiology here at McMaster allows me to do. I do some pretty good science, we think that, you know, I can chalk up a baseball a short distance, and I hit my lab, which is in effect a gym. So I kind of get the best of both worlds.

Ted Ryce: Yeah, and what I love about your work, because I’ve quoted your work a lot in the articles that I write having to do with protein, how much protein should we eat, the timing of protein. And what I love about your work and love about what you do is that you give us super practical advice that we can take away and start using in our lives right away to get better results. And I really appreciate that about you, man.

Dr. Stuart Phillips: Well, those are generous words, and thank you for them. I often find, you know, I always say I suffer from an inferiority complex. But as scientists, we’re always worried, I think more so today than probably even 5 or 10 years ago, about the translation of knowledge from the work that we do. And I do know that some people pay attention to what we do. And there are some practical implications.

So it’s nice to hear that, you know, it’s not good enough these days, I don’t think any way to publish a scientific paper, and then to just have it sit in the journal and only be read by a few other scientists.

And so, open access and trying to get things out on social media are things that I’ve kind of worked hard to do, and then emphasize that to my students and try and get things out. So I’m really pleased to hear that. Well, at least a few people have said it. So you’re not the first, but t other people are listening, so thank you for that.

Ted Ryce: Yeah, absolutely. And I think it’s really important, because I’m not the guy to be in the research lab, that’s not where my journey took me. But we need each other, because this following of people who are very confused about nutrition world, and people say so many things in my field. People, unfortunately, with a big following like me might say something and really confused someone and it may not be so accurate. I’m just curious. I mean, I wasn’t going to ask you about this, but it’s in my head right now and I think it’s important to go to, what would you say to people about the conflicting advice about nutrition in general?

Dr. Stuart Phillips: Yeah, it’s tough. And I say to the undergrad students that I teach, and I say to my grad students, I said, “You know, you’re living in an age where information is coming at you at an incredible speed and from a variety of mediums. So it’s tough to what I call, put the filter on and figure out what is the signal, the true message, and what is just noise.” And I think the ratio of noise to actual signal has gone up tremendously.

I don’t mean to be trite, but I always say to people that commentary about science is relatively speaking, easy. Science is hard, during science is hard. And communicating it in an easy to understand way may actually be even harder. So the problem with nutrition, because everybody eats food, it evokes a very emotional reaction as well, as you know, let’s try and figure out what science says.

And let’s face it, in science, there are some times conflict as well in terms of one person says this, one person says that, and so then the translation sort of increases that noise level and then you’ve got it from different mediums. And so really, I’ll be honest in saying that particularly where nutrition is concerned, the confusion is it’s not earned, but it’s definitely understandable. And it’s unfortunate.

So, research, trust your sources, all the things that I tell my students, but a lot of people don’t have the time for that, and they’re trying to get the signal right away. And it’s tough. I’d be fair and honest in saying it’s really tough.

Ted Ryce: I’ve consciously made a decision to focus on getting more people like yourself on who are actually doing the research, and who a lot of us fitness professionals are basing our recommendations on. So I really appreciate that. And what you said is true

Dr. Stuart Phillips: It’s why I’m here.

Ted Ryce: Yeah, absolutely. So let’s hop into it. Let’s talk about today’s topic, which is protein. And let’s clear up some confusion about it. So many people have heard that they need protein to build muscle, protein is important. But I would love in your own words, could you please describe, why is it so important?

Dr. Stuart Phillips: Yeah, so I generally use an analogy in the situation that I think most people tend to understand. And if you imagine that every protein containing structure in your body is like a brick wall, and the bricks to build the wall are part of your diet. So the protein that you ingest is serving to increase the number of bricks that are going into the wall.

But at the same time, your body has a turnover mechanism that’s taken bricks out of the wall, old damaged bricks and bricks that don’t work so well. And a few of those bricks we lose every day. So we have to put new net bricks into our system. Muscle is probably the easiest one and the one most people go, “Oh, yeah, okay, that’s where most of the protein is,” that’s probably true.

There are proteins everywhere, even bone, I think a lot of people don’t realize is just about 40% by composition, actually protein. It’s not just a piece of chalk, so to speak. So there’s this constant protein turnover that we have going on. And so bricks in and bricks out is really what determines gain or loss of, you know, you name that predominantly muscle mass.

So I think that’s what most people, I find that they can work with and understand. And so because there’s a net loss of bricks every day, we have to keep eating protein, and really have all of the bricks, which we call them amino acids, which compose protein, there are nine that are essential. So in other words, we can make all the other bricks 11 out of the 20 that are there, but nine of them, we have to get from the protein that we eat. So that’s kind of the analogy I use, and I use it with my students. And I’d like to say most of them understand, hopefully.

Ted Ryce: I’ve heard you say that or use that analogy before, and I really appreciated it. And I think it’s a great one. You can visualize someone building the wall on one side, while someone else is at the other side busy taking them down.

Dr. Stuart Phillips: Taking the bricks out, yeah.

Ted Ryce: And if you don’t put more in, or at least maintain what you have, which I want to get into next, you start to lose protein, especially when it comes to muscle, that’s a very bad thing metabolically, and if you’re interested in looking good in a bathing suit, or, you know, fat loss. And I’d love to ask you about something that you’re very familiar with and I’ve heard you talk about a lot, which is the age related muscle loss or the progression of muscle loss as we age, sarcopenia. Can you talk to us about that, and then we’ll get into what protein has to do with it?

Dr. Stuart Phillips: Sure. As you said, most people are of the belief, and I would say belief, but the theory is that, you know, an empirical observation, as we age, our muscle mass tends to decline. Most of the population base graph say that probably start somewhere in our late 40s, early 50s. But the older I get, I keep pushing it back a little bit.

We’re not really sure how much of that is actually chronological age as you get older and how much is inactivity. What we tend to think is that the more active we are, we can kind of flatten that curve out as opposed to it sort of dropping off a little bit faster. So the axiom, “Use it or lose it,” is in full play.

So I don’t think that anybody can obviously turn back aging, but you can improve the rate of loss by being active. So the phenomenon and the word people use is sarcopenia and that age related muscle loss, it’s responsible not for just the loss of muscle mass, but also for the loss of muscle strength. And at some point, you begin to lose enough strength that activities of daily living like getting up off of the chair or simply moving around your own house becomes a problem.

Ted Ryce: Yeah. And I’ve shared this story a few times where I was taking a flight on this small plane through the Grand Canyon. And there were six people with us. And two of the six people were an older couple and not that old, and they were having a good time, you know, probably retired, and we got a chance to take turns sitting in the cockpit. I flew in the cockpit on the way there.

And on the way back, this guy, he was trying to make his way into the cockpit. And it’s not like a nice plane with a very easy to walk up set of stairs, they were kind of steep. And it took him like several minutes and all his upper body strength to pull himself into that, and I’m just thinking, this guy, aside from walking, probably doesn’t do too much.

Dr. Stuart Phillips: Yeah. And I think, you know, that’s a situation where you’ve observed, it’s a task that obviously, this person doesn’t have to perform very often. But instead of stairs like this, it’s like this. And then the bottom line there is that everything is, you know, it’s a much bigger effort for that person to accomplish that task.

So these are things that we sort of take for granted as not really being that big a deal. But as soon as somebody is challenged, it begins to tap into a reserve, or an area where they’ve never really gone. And you can see that they’re beginning to struggle, for sure.

Jk, Yeah. And we’re using examples of people later on in their life. But can you tell us a little bit about what or who sarcopenia might be affecting? Or if they’re inactive, at what age might it start to affect us if we’re not moving our bodies enough?

Dr. Stuart Phillips: Yeah, it’s an interesting question. And we do a lot of studies where we write on a consent form, we’re looking for people between the ages of… I don’t want to say aging starts at 65, that’s retirement and it’s quite frankly, a lot easier to recruit people 65 and older, but I can find some 65 and 70, and even up to 75 year olds that come into our lab, and they look metabolically—they’re older, you can tell, but metabolically and the way that their muscles work in strength compared to their mass is, they look pretty much like 35/40 year olds.

Sometimes we’ve had 35/40 year olds come into the lab and because they’re so inactive, they’re generally overweight as well, they look a lot more like some 65 and 70 year olds. And so, chronological age is one thing, but it’s almost as if your level of activity determines—and I’ve heard metabolic health people say, and whatever that is, whatever that construct really defines, I don’t know. But generally speaking, people that are older, who are active, they’re just on less medications.

And I don’t need to give you my examples. But the literature would bear this out with lots of observational data about what physical activity can do for you, for sure. So when does it start? I think it could start, in fairness, in some people, even in their 30s, and I know that presses a lot of people, the less active you are, the more problems that tend to arise. And then I think that just compounds itself and it becomes a real issue.

Ted Ryce: Yeah. And later on, I want to talk about the whole dieting and sarcopenia thing and how, if you’re using the scale weight, and it’s going down, and you’re really happy, it could actually be something that’s actually bad for your health in the long run. One thing I want to ask you about is sarcopenic obesity. Can you explain that because that? Is that the skinny fat people that are usually, or…?

Dr. Stuart Phillips: I think that skinny fat…I mean, some of these terms, I kind of smile, but yeah, sarcopenic obesity, some people like term, it’s the combination of their sarcopenia muscle loss, but then you’ve obviously got a lot more body fat, and that puts you in the BMI range where you’re obese.

Somebody who has that type of syndrome, and the best thing I can point to is to say, if you look at a cross section of their thigh, so it’s a sort of a round image and there’s some bone in the middle. And most people, they have a muscle like this, these people have a tiny little muscle in the middle of their leg and then the rest of the leg is made up...

Ted Ryce: Right.

Dr. Stuart Phillips: That’s the person who they look sort of bigger and you think, okay, well, they should probably have more muscle because they’re big, but actually they don’t and so it’s probably a person that very early on, did very little, may have some metabolic disease, some type of vascular disease or type II diabetes.

And then everything begins to sort of spiral down and the inactivity and everything else, I think becomes an issue and that muscle loss rate is now you’ve got a curve like this instead of sort of being flat, and they get themselves in all kinds of problems, because the ratio then if they’re fat to their lean mass becomes a real issue and metabolic disease is an inevitable consequence, for sure.

Ted Ryce: I think it’s a really important. I’m glad you said that, because I feel like some people who may not be as, I guess, nerdy as me and reading about the difference between body fat percentages, as opposed to just weight because most people just focus on weight, it’s simple, you step on the scale in the morning, they may not get that, oh, the scale may represent something or even fitting into my clothes.

But as you said, if the circumference of my thigh, if the size of my thigh, if most of that is fat compared to muscle, it’s still okay, you can fit into your clothes, but you’re on your way to a bad place here, metabolically speaking.

Dr. Stuart Phillips: Yeah, I think so. And I mean, I always talk about thighs and legs, mainly because when it comes right down to it, and people say what’s the most important lift? And I say, well, imagine yourself sitting on a chair and then trying to get up. Because once you can’t do that, then you know, you can’t get off the toilet, you can’t get off… I mean, just everything becomes a problem, right? And you’re looking at somebody needing to care for you full time.

So I don’t like to be trite, but there’s a lot of use of things like hand grip, and I’m like, okay, really, your leg strength is going to be much more important in older age than your hand grip strength, might not be able to open the car, but if you can get off a chair, you’re in a much better place. And you can’t do that if you’ve got a little muscle inside of a big leg.

Ted Ryce: Yeah, that’s well said and so important. Let’s talk a little bit about how protein interacts with or affects sarcopenia. So what is the relationship there, Stu?

Dr. Stuart Phillips: I think the easiest way… and I always use a line that say, “Exercise is king and nutrition is queen, you put them together, and you’ve got a kingdom.” I know, I’m obviously parroting back, Jack LaLane, but I think it’s very apt in this situation. Exercise, if you like, just makes your muscle very receptive for growth.

So what it does, you can imagine this, that, once you’ve exercised, it’s the protein that you provide then to your body, it’s used far more efficiently. And there’s a net greater influx of bricks in the wall. So, empirically, we see this and we call it hypertrophy, or muscle growth, and people’s muscles get bigger with limit. And then a certain point, obviously, protein is then just maintenance.

But in older people, when you’re coming in on the downside of the curve, the more protein that you eat, we’re of the opinion, at least or of the theory is that just helps, again, the curve a little bit, probably not as much as activity, I’d be fair in saying, but it does help, particularly as you get older. For some reasons we’re still trying to unravel, there is in older people, in all likelihood, because of their loss of muscle, a greater need for protein.

So that might be contrary to what a lot of people might tell you, but I think the evidence is beginning to build now to say that these older people, we don’t need to feed them low amounts of protein, we need to feed them probably higher than we did when we were adults. We were sort of on that plateau, because now we’re starting to go on the downside. And again, when does it start? I don’t know. I’ll tell you that I focus a lot more on protein in my diet than I used to, that’s for sure.

Ted Ryce: Yeah. And that’s another thing that we should go into, because some people say, for longevity purposes, that we should perhaps remove protein from our diet because of a mechanism that may cause cancer to either grow faster or even start. But before we get to that… or actually, let’s get into it right now.

So I just want to be clear on something you said because you said that all this stuff that we’re going to talk about with protein, it doesn’t matter unless we’re exercising. And one thing I want to be clear is you’re talking about weight-bearing exercise, not necessarily swimming, for instance, or I guess swimming could be okay if you’re doing sprints, but could you just qualify that, please?

Dr. Stuart Phillips: Sure. So my take on exercise or activity is that it…the biggest drop we have in risk, when we perform physical activity is going from nothing to something. So if you’re doing nothing, then you better be doing something, that’s much better. There’s a big drop and risks robbed from the couch potato to somebody who even goes for a walk for 20/30 minutes a day.

But everything sort of beyond there, begins to incrementally add on and reduce your risk even further, probably to a point, you know, if you’re running 100 miles a week, or you’re lifting six days a week, I don’t know that you can squeeze much more out of the cloth, you’ve got most of the water out.

But let’s just say is that we’re looking to optimize your health, so we need to do something to maintain our fitness, whether that’s sprints, or we like to walk, or we like to run, whatever it is, but at some point, strength and muscle mass are going to become important. So I think you’ve got to tie the two of those things together. In my opinion, you need both.

So you know that having been said, swimming is good. Don’t get me wrong, you’re doing your thing and like swimming and that’s all you really do. Perfect, but you don’t bear body weight when you swim, so it’s not a great stimulus for your muscles. There is a little bit of resistance water it’s not just waving your hand through air, but it doesn’t do much for your bone and it doesn’t do much then for your skeletal health.

And so the reality is, or bike riding, it’s the same sort of thing—still very, very good for you, don’t get me wrong. But as we get older, I think you have to think about these two things coming together. So I’m probably a little less enthusiastic about putting down any form of exercise. Because when we look at statistics, most people are doing next to nothing.

Ted Ryce: Right.

Dr. Stuart Phillips: So I’m like, “What do you think he can do?” And they’re like, “Oh, I can probably do this.” And I’m like, “well, then do it, get out there do it. Because it’s much better than zero.” You know, the people who are doing between zero and probably about 50 minutes of activity a week, they’re in real, real trouble. No question.

Ted Ryce: Yeah. Thanks for clarifying that. And it is an important point. I think people like myself, we tend to say, “Get in the gym and lift some weights,” when it’s like, well, they’re not going to do that, the person on the couch, because they probably would have already been doing that. How about just get them taking a walk?

But at the same time, once you get moving, and you’re looking to optimize your health, definitely the weight bearing exercises, especially—you gave a great example, when you can’t get out of the chair, because you no longer have the ability to push yourself up from it. Stu, really quick story, I worked with a CEO who is riding this recumbent bike all the time. And he had a Porsche, which is very low to the ground, very difficult to get into.

Dr. Stuart Phillips: I’ve seen that, but I’ve never really had my own experience. I’m just going to be…

Ted Ryce: Yeah, sure. Of course.

Dr. Stuart Phillips: I understand.

Ted Ryce: Yeah. And he was saying, he’s like,” I’m having trouble. You know, I’m in good shape. I ride my bike.” I think he rode it five days a week or something. He’s in there in the gym riding five days a week. And he looked muscular, too, which is interesting. I don’t want to get into the sarcopenia versus dynapenia thing, as we have already so much to cover. And I asked him to do a squat and it was just like, he couldn’t get down. So it’s just important to keep that functional being defined as like your ability to do your daily living, the things that you do in your day.

Dr. Stuart Phillips: Exactly. And I think that that’s the real key, isn’t it, is the certain people, like the guy who had never really gone up the steep stairs, if you’re never really challenged by something, and then all of a sudden, you have to do it, but your guy on the recumbent bike, probably the heart and the lungs, not in bad shape. So he’s okay, from that perspective.

And maybe that if he’s doing it five days a week, allows him to stave off a little bit of weight gain. So maybe he does look okay. But then movement wise, he doesn’t have the range of motion, and he doesn’t have the strength once he’s down there to sort of push him in. And he’s always having problem getting out of his car. I mean, it seems a little bit ridiculous.

But somebody has to…If there’s a big step in front of their house, then you better make sure you practice doing something like that big steps so that you can handle it. But if it’s never there, then you’re never challenged and you never really do it. So it’s specificity of the actions that you’re doing. But it’s a great example of somebody who becomes limited in something that they want to do, simply because they’re not practicing or challenging themselves enough to be able to do it.

Ted Ryce: Yeah, absolutely. Thanks for clearing that up. Because I think some people are told, or a lot of people are told hey, you’re, you know…And there’s a lot of research showing your vo2 Max highly correlated with longevity, but if you get to the point where you can’t get out of a chair, you have trouble using your legs, it’s just very difficult to get into good aerobic shape if you have that sort of loss.

Dr. Stuart Phillips: I want to say that with age, I think the two of those things come together and become more important. Maybe at a certain point, if you had to run around at a soccer match, or you were doing something that required strength and power in a particular sport, you practice for that. But as we get older, people asked me, they said, “What are you training for?” I said, “I’m training so that I can not have this, this or this and I can do this, this and this as I get older.”

I got three boys, I’m planning on being able to hopefully—I’ve lost it with one, he’s bigger and stronger than I am, but I’m still bigger and stronger than two. And I want that edge for as long as I can. But at some point, I want to be able to chase their grandkids as well. And I mean, it seems trite, but life changes. And I think those two things, the fitness and the strength begin to come closer and closer in terms of you need them just to do everyday things.

Ted Ryce: Yeah, so important. And like you said, it’s no…You say it’s trite. It’s not what we’d like to admit about getting older.

And I’m starting to think like, okay, if I’m working out hard, but my knees constantly inflamed, and that’s going to lead to me not being able to get in shape or stay in shape. I’m going to go down really quick, even though I’m feeling real badass now, right?

So I’ve completely changed the way I think, and I think more about that. And I think that it would be a good challenge for people who perhaps don’t think like that right now to think about how you want your life to be and what you want to be able to do in your life. And make sure that what you’re doing now is leading you to that path.

Dr. Stuart Phillips: Absolutely. People in their 40s, and I know it’s a…again, with the vision of hindsight, you become more wise about these things. But the ability to create a picture of…A guy who I interact with on a frequent basis calls it “The vision of your future you and where you want to be.” And in your 20s, you have no idea because 50 just seems like, you know, who’s 50?

And then all of a sudden, you are 50 and you’re like, “Jesus, I’m 50, so I’m the old guy.” And you’re thinking, “Well, geez, I would like to live and be active and independent into my 70s, 80s and beyond that.” That requires a plan now, that’s not just going to happen lickety split. It’s always easier when you’re younger, and I get it, no problem. And so people talk about lifting these weights in. And I used to shift a lot of weight around. But I can’t do... If I can’t walk the next day after doing a big squat workout, why do I bother?

Ted Ryce: Absolutely. Yeah, something for everybody to think about. Stu, let’s change gears a little bit. Let’s get into the myths about protein. We’ve talked about how exercise is important. And protein helps get those building blocks into our muscles so that we can maintain or perhaps build our muscles. But there’s a lot of myths out there about protein.

Let’s start with the biggest one, which is something that—what that health documentary kind of pushed in people’s faces. And I’d like to hear your perspective on it, which is protein in cancer. So we know that IGF-1 is a growth factor and it may be implicated in cancer, somehow we know that eating protein increases IGF-1, even if it’s vegetable protein, by the way, for my plant based friends, what can you tell us about where the research is with that?

Dr. Stuart Phillips: Right. So let me just say that I was trying hard not to laugh too hard when you talk about “What the Health.” It’s a show that I think verges a little bit on… I call it science porn. It’s sort of fun and titillating at some level, but it just crosses over and over exaggerates a lot of things, because that’s how the show gets his followers and creates the buzz that it does.

It tends to polarize people, which is always a sign. I think the opinions are extreme. If you align with them, of course, then great. In the next episode, they’re aligned in the different direction with some of your feelings about. So I hate to digress, but let me just say simply that you’re right.

The theory is that protein stimulates the release of insulin-like growth factor, IGF-1, and as its name says it’s a growth factor. The persistently elevated IGF-1 then is a way that would trigger or promote growth of cancer. So in experimental models, so when we talk about rats and mice and all kinds of things, this is where this theory begins to sort of take hold.

There’s no clinical trial in humans, it’s all what we call observational data. So we’ve got data on a person at age 20. And data on the same people at age 50. We follow them for 30 years, we see how many people die, we see that they’re eating more protein, and then we try, and I emphasize the word “try” to filter out everything else that happened in their life, and pin the fact that they died from cancer on protein.

So I just want for people to appreciate what these studies actually do. My own opinion is very, and I mean very difficult to hang protein out as the reason why these people got cancer. People get cancer for lots of reasons. We all know about environment. We all know about genetic predisposition. And we know about a lot of other factors.

And the one study, and I love to mention this, is to say that, in an examination, again, a huge cohort of people, over 60,000 people, the 26 most common types of cancer, 13 of them, you had a lower risk, if you had greater leisure time physical activity, that’s not big heavy weightlifting or 100 mile runs or bike rides. That’s just leisure time physical activity being greater.

So you did a little bit more. But like I said, not nothing, you did something. And the highest in terms of leisure time physical activity versus the lowest, 13 out of 26 cancers produced. So is it causation? Does exercise cause the other one? We don’t know. We can’t say that, and neither can the IGF-1 and cancer people.

So I suppose what you would like to say is the, pardon the pun, but in the smoking lobby, and the ant- smoking lobby, during the 40s, 50s, and 60s, desperately wanted to say there’s no connection between smoking and cancer. But the smoking gun, so to speak, is, well, the people found it because they got the lab tests, they got the observational evidence, and they said, “You know what? There is, and the evidence is too strong to deny, you got to put a warning on your cigarettes.”

30 years later, and I remember listening to the Surgeon General C. Everett Koop when he was in office saying 30 years from the time that those warnings were put on cigarettes campaign, you started to see a noticeable decline in cigarette smoking. So when somebody says, oh, and IGF-1 and protein and cancer, I’m going to put it in perspective for you. A nonsmoker has this risk of cancer, and a smoker has a risk that is seven times higher. That’s a pretty big increase.

So if one person gets cancer here, lung cancer, a smoker—off the chart, right? It’s up here somewhere. So IGF-1 and cancer has what they say risk ratios or there’s somebody with a low protein intake. And here’s somebody with a high protein intake, and it’s about 1.2 to 1.3 times, and these people would like for you to believe, and I stress the word “believe,” that it’s all about protein.

And I really struggled with that. So, I don’t want to say that it’s not there, but I think that there are a lot of other factors that come into play, and for you to pin it on “find that smoking gun for protein,” nah, it’s just not there. It’s an interesting theory. I think a lot of people would like to push it as a true reason. And they argue about evidence, but I think when you sum the totality of the evidence up, I think it amounts to not very much, to be fair.

Ted Ryce: Yeah, thanks for that. And I asked to because I’ve heard from a couple people, or one in particular, he asked me about protein fasting, someone in one of our coaching groups, and I was like, “You mean only eating protein and nothing else?” That’s where my mind immediately went to. And he was talking about not eating protein at all for a day. And I said, that sounds like a really bad idea. Well, maybe you can get away with not eating any food at all: protein, carbs or fat for a day. And then we got into talking and that was the reason concerns about that. What about protein and kidney damage? That’s something that even dieticians will say sometimes.

Dr. Stuart Phillips: Yeah, again, I get on my soapbox and I rant about certain things. And so we need to set the record straight on this, and it’s the clearest example of what I call flawed circular logic. And so somebody who has kidney disease, their beginning a pathway to what we call kidney failure, they’re put on a low protein diet and what we do know about people who are on that, they live a little bit longer. Fair enough, you know, the kidney is beginning to fail, so it doesn’t want to filter substances that are due to protein and lots of other things.

But the bottom line is, that’s the observation. So then a lot of people say, “Uh-huh, well, this person who has kidney failure is on a low protein diet, they live longer. Therefore, it was protein that causes kidney failure.” And I’m like, “No, that’s not true. You can’t say that, unless there’s some data showing that higher protein, at least maybe is associated with kidney failure, and the amount of data that shows that is next to nothing.”

I don’t want to say we’ve got a study in process, but we have, and we can’t find the association either. So it’s a non-starter, non-sequitur, to use the expression, to say that one begets the other only because one is used in the treatment of the disease. And there’s actually no evidence that links the two, even the World Health Organization and the Institute of Medicine, which sets in the United States and Canada, what we call dietary reference intakes, has that in both of their nutrition tax when they talk about setting protein intake levels. So anybody that says that is actually grossly misinformed about what physiology actually underpins the development of renal disease, or kidney disease.

Ted Ryce: And unfortunately, there are a lot of people—even I think I sent you a New York Times article in our back and forth emails, and it was talking about that how, “Oh, we don’t need so much protein, stop eating all the protein.” And although I enjoy some of their articles, that one just made me shake my head.

What about bone loss, because that’s this is something that’s probably newer, at least that I’ve heard about in my 18 years in fitness, that protein is very acidic, when you eat it, it causes this acidifying process, whatever happens, right, the uric acid, I guess, and then it starts eating your bone. And we have women who listen to the show, and the guys who listen to the show have wives and girlfriends. And women in general are very concerned about this. And they may not eat protein as a result, what can you tell us about the connection there?

Dr. Stuart Phillips: Yeah, I mean, as you said, the idea that more protein— and even like a high grain intake is associated with and acidification of your blood. And then your bone as a result tries to get rid of the acid, if you like, by actually releasing calcium from bone. And that’s the theory, they call it the acid ash, and the ash is the bone side of things hypothesis.

What we do know and as I said earlier, is the bone—and I think a lot of people just sort of go, “Oh. It’s not a stick of chalk, it’s not just calcium. If it were a stick of chalk, your bones would snap all the time. So, protein gives bone the ability to bend—not an awful lot, but enough that day to day things don’t snap. I mean, if you ever snap a piece of chalk, easy, right? Put a little bit of protein in there, it kind of bends just enough to make a difference. So your bone has some protein, and I think that’s important to mention.

The two most important things to bear in mind from a bone health standpoint are clearly calcium and vitamin D, hard to get in certain parts depending on where you are and how much sun you like to get. And then everybody tells you to wear sunscreen because you’re going to get melanoma, etc, etc. So everybody puts sunscreen on. So probably we’re in a situation where you have to take vitamin D as a supplement. It’s one of the only supplements I take on a regular basis and living as far north as I do, we get about five useful months of sunshine per year. So we’re just about to run out of it now. And it does start at the right latitude.

So once you get calcium and vitamin D in intact, and so that’s about 1000 milligrams a day for most women. It’s arguably, and I won’t go off on a vitamin D rant, but let’s just say it’s about 600 IUs to maybe 1000 IUs or some people say up to 2000 but we’ll gloss over that a little bit.

Once you do that, then protein is actually some supportive of bone health, there’s really no evidence, causal evidence that shows the protein begets more bone loss and then predisposes you to more fractures. So rate review the National Osteoporosis Foundation in the United States, this came out probably about four or five months ago, saying that if anything, protein is associated with better bone health. So it’s the opposite of what the protein begets acid, acid begets bone loss, people would want you to believe.

Ted Ryce: Yeah, that’s very interesting. I fell into that for a little while, I guess, maybe 10 years ago or something. And it was something I was very concerned about, the whole acid/alkaline thing. And now it doesn’t seem like it’s ever really taken hold, at least in the scientific literature. There’s some people still wearing tin hats that talk about it.

So we’ve talked about the importance of protein. We talked about sarcopenia. We talked about how this all works in conjunction with exercise and some of the myths surrounding protein. Let’s talk a little bit about how much protein should a person actually eat. Now, I’ve done some… I follow Alan Aragon and you and Brad Schoenfeld, all these other people. And there was this big meta analysis of I think, 49 studies showing that 0.73 grams per a pound... Sorry, I know you’re a metric…

Dr. Stuart Phillips: You’re going to make me count. I got my pen out here, I’m going to do some quick math. Yeah, that’s about right.

Ted Ryce: Yeah. I believe that was the amount. And that was for building muscle and for exercise. So for someone listening to this, who’s working out hard, is that what they should eat? And what about people who aren’t working out as hard, what amount of protein should they eat?

Dr. Stuart Phillips: Yeah, so the analysis that you’re referring to, and it was one that we collaborated with Brad and Alan and Eric Helms, Jim Krieger, great bunch of guys to work with, and we really wanted to bring them in and sort of get their expertise mainly what their thoughts were around this type of passage.

So, pulled together all this data, 49 studies, 1800 some odd people and basically said, when you take extra protein, do you gain more muscle? And the short answer is yes, it’s not as much as most people think but it’s there. I sort of look at it this way, is that the analogy I always use is to say is that, you dip a rag in some water and you’re squeezing out the water, that’s the outcome. In this case, it’s muscle gain, or whatever you want to think about it.

In the first few twists, you get a lot of water out. And then more you sort of squeeze on the ragged, there’s a little bit less water out, and there’s a point where it’s so twisted in on itself, and you can do all you want, it’s just dripping little bits of water out. Protein probably exists on a curve where it comes up, and then at a certain point, it begins to plateau off, and then you can eat more protein, but you can’t put any more into your muscle.

So if you said 0.7, or there abouts, grams per pound, which averages out to about 1.6 grams per kilo. Now, there are a few people who might be able to go up and above that, and you can squeeze a little bit more out. But I think it’s a real diminishing return. Most people, most mere mortals people like myself included, who aren’t really looking to gain a whole lot of lean mass— I’m in this complete maintenance phase, that’s all I care about—are thinking, what, somewhere in about 1.4/1.5 grams per kilo, so translate that back, it’s about 0.5/0.6 grams per pound, you’re probably in a good range there. You’ve got to have a whole lot of things in your diet and shape as well.

We talked about calcium, we talked about vitamin D, all these sorts of things. But really, protein intakes in that range, which are pretty easily achievable for most people are probably going to get the job done and a lot of the job done for most of the people that are out there be, to be fair. So I like the 0.5, 0.6, up to 0.7. And by all means the message is still, you can eat more, and your body can digest more and you can take it in, but you don’t really have a place to store away protein. It’s not like fat or carbohydrate, which unfortunately, we’re very good at putting and turning into fat.

But protein, because of that nitrogen, it’s different. And your body just struggles to kind of…It’s not like there’s a little protein bag or something. You’ve got to put it somewhere or your body gets rid of it. And that’s you know, you’ve heard people say, too much protein, you’ve just got expensive urine. So it’s half true, because a lot of it, that’s where it’s ending up, that’s how we get rid of most of it.

Ted Ryce: Yeah, important to know. And one thing that I think is also important is the timing of protein, which you and your lab have done a bit of research on. I’ve talked about this study where you divided up 80 grams of protein into eight10 grams servings, or two 40 grams servings, or four 20 grams servings, and you found that four 20 gram servings increased protein synthesis.

Now protein synthesis is all types of protein in our bodies, not necessarily muscle. What can you tell us about that study and the importance of protein timing and breaking up our protein throughout the day?

Dr. Stuart Phillips: Right. So really short, and not to confuse anybody. The study that you’re mentioning, it was about measuring muscle, but it was a very short study, it was basically only one day. And so we studied people on three occasions when we were looking at those measures. So we kind of went inside the muscle and looked at the actual rate of bricks going into the wall. So muscle protein synthesis, as you say.

A lot of people, they sort of go, “Oh, well, it’s pretty contrived and it’s controlled conditions.” Absolutely, I wouldn’t disagree. I think that…And again, I’m going to defer to my friends, Brad and Alan and Tim Krieger, who have done a great job through summarizing all the studies and looking at protein timing.

And it does appear that you know, particularly around the exercise about is a good time when your muscle is receptive, protein say. But I think the important point for understanding for your listeners is to say that the meal that tends to be the lowest in protein per day, for most people, is breakfast. And if you think about it, you’ve just gone to sleep, you’ve slept for, you know, if you’re the nuclear sleeper, eight hours, then you get up.

And the first thing you consume is low in protein. When really, what you want to do is to be able to tweak the rate at which muscle protein synthesis or bricks into the wall is going on, and get the process started. And so the spacing of your breakfast meal to your lunch meal to your dinnertime meal, usually it’s low protein, moderate protein, and then very high protein at dinner. And probably what it should be is that those are much closer in protein content, and that they’re sort of evenly spaced throughout the day so you get this periodic delivery of bricks, so that you can push them into the wall.

A lot more work needs to be done to confirm that sort of theory that I’m talking about there. But there is, and again, how much stock you put in, an observational data in older people, that people who consume protein like that throughout the day, tend to have more muscle. And so I’m beginning to think that that theory has some legs, and hopefully, we’ll be able to contribute a little bit more data in that area pretty soon.

Ted Ryce: So very cool. And it’s not much effort to change that, just having a bigger or a larger amount of protein at practice. What do you think about the research on pre-sleep protein?

Dr. Stuart Phillips: I think there’s another area because it’s sort of…And I mean, part of me begins to think that the glass of milk before you go to sleep, it helps you sleep. I’m not sure whether that’s true. But I always remember when I was a kid that I had a bedtime snack, and it was almost exclusively, it was a bowl of cereal.

So there’s a lot of milk in there. There’s some carbohydrates, obviously, from you know, usually Cheerios or Shreddies or something like that. But I don’t know, I think we’ve probably been doing it and we didn’t even realize it, and kids who are growing and they’re athletic as well, like, it just becomes, “I’ve got to eat something before I wake up starting.”

And so I think that there’s some evidence there to suggest that it’s not a bad strategy. It’s one of these, you know, we’re asleep for eight hours, or we’re in our beds for at least eight hours or maybe 10, even longer for some people. And it really is a time when, because we’re not eating, everything, the rate at which bricks are coming out of the wall versus going in begins to shift, and you lose a very, very small amount of muscle.

And so if those periods are prolonged, maybe delivering protein before you go to sleep isn’t a bad idea. Again, a lot more work to be done. But I think that that theory has as a pretty good underpinning and hopefully we’ll see some more work on that in the future.

Ted Ryce: Yeah, I’ve been trying to get Jordan Tromelin on the show to talk about it.

Dr. Stuart Phillips: Oh, yeah.

Ted Ryce: But he is actually running some more studies right now.

Dr. Stuart Phillips: Yes. Jordan was over in our lab this summer. And we had him tell us a little bit about what he’s doing. And yeah, I mean, between him and Luke and Mike Ormsby of Florida State, they’ve got a really good lock on that science. And I’m really interested, whatever those guys have to say anytime, for sure.

Ted Ryce: Very cool. I know we only have a few more minutes, I’d like to ask you about protein quality, because if we look on a bag of beans, it has a lot of carbohydrates in it, a little bit of fat, but there’s protein in it as well, though not as much as the carbohydrates. If we look on nuts and seeds, there’s not as much protein as fat, but there is a bit in there. And then we get something like a steak where it’s a lot of protein. What can you tell us about the quality of protein and how it’s important to building muscle and maintaining muscle?

Yeah, so I think the rider statements before I talk about it are, I don’t think it’s as big an issue for kids that are growing, because growth tends to happen, regardless of your protein quality, unless there’s something really poor about the quality of protein. So we’ve seen that obviously, in kids in food challenged areas, in economically challenged areas.

I think as we get older, I think protein quality becomes more of an issue for the reasons that we’ve talked about in this podcast. So what I want to say is that you have to think about your food, as you know, beans, and nuts and seeds do contain protein, they contain a lot of other things, too. They contain dietary fiber, which is particularly good for your cardiovascular health, predominantly, maybe through lipid lowering, or all kinds of other things. Great for your gut health.

Meat, and eggs, and milk and dairy products contain protein, but they also contain a number of other nutrients. So I tend to think of those as sort of being what I call nutrient dense protein sources versus not as nutrient rich, all kinds of other things. And your diet is the sum total of everything that you eat.

So I don’t say well, you need to have this or you only do this, and I’m very well aware that vegan, vegetarian, people do just fine, thank you very much, and no problems at all. But I do think that when you’re getting older and you’re planning, the amount of calories that you’re going to take in, you also need to get all of the other nutrients that you need to be a full functioning person.

And so it requires a little bit of judicious planning about you know, am I getting enough iron? Am I getting enough vitamin B 12? Am I getting enough zinc? Am I getting enough calcium? Because all of those are what are called “nutrients of concern.” It’s more difficult for older people, who by their very nature, consume less food, to get in their diet. So it’s more of an issue for that type of population.

Having said that, I think food enjoyment has sort of been left out of so many equations these days. And so I don’t like to harp on one particular way of eating versus another. But if you enjoy what you eat and it’s doing you good from a health standpoint, then there are 100 or 1001 different ways to eat food, no question about that.

Ted Ryce: Okay, can you at least mention the leucine content of animal protein or whey protein and why it’s more powerful for muscle stimulation than plant based protein?

Dr. Stuart Phillips: Yeah, for simple reasons, or for reasons, I should say, that we don’t understand—not simple reasons, probably—leucine is one of the single amino acids out of the 20. And it’s one of the nine they’re essential. It’s sort of like when your muscle receives leucine, it’s like turning on the light switch for the protein synthesis process.

So the bricks start to go into the wall much more rapidly once Leucine is around. When people are inactive, or they get older, or they have things like type II diabetes, metabolic disease, they need more leucine for that process to happen. And so as I said, I think then when you talk about proteins that are higher in leucine, and generally speaking, they tend to be higher quality protein, so of the animal derivative, so meat and eggs, and no proteins, whey and casein.

Whey is off the list. And it’s, again, probably reasons to do with where it comes from, which is milk, which is a substance designed to sustain life when you’re doing the most growing you’ve ever done. It’s very rich in leucine. And so those are things that probably older people should think a little bit about getting into their diet. I appreciate that taste becomes king.

So there are some products out there that I say, you know what, this isn’t a bad effort getting some of this into your diet. I’m not a huge fan of using supplemental amino acids for the main reason, I think that A, they’re expensive, B, they tend not to taste great. And C, it’s only really about leucine. A lot of people go branched chains, branched chains, and I’m like, those three branch chains, forget about the other two, just focus on leucine.

So leucine rich proteins or nutrient rich, two thumbs up, that tends to be, and it’s not a plug for the dairy or the cattle farmers or anything. It just that the reality is it tends to be meat and dairy and egg based protein.

Ted Ryce: Yeah, you’re a shill, aren’t you, Stu?

Dr. Stuart Phillips: I’m total shill. Yeah. The dairy guys over here are about to pay me off, for sure.

Ted Ryce: You know, I got called that recently after I did this article on What the Health because I tried to take a balanced approach. Anyway, I don’t want to get too off topic. I know you got to go. Stu, this was an amazing interview. And I think it was a great introduction to your work and to understanding the importance of protein. However, I’ve got like two hours more of questions to ask you. But thanks so much for coming on. We definitely have to do this again.

Dr. Stuart Phillips: My pleasure. Yeah, absolutely.

Ted Ryce: Yeah. And talk about peak plasma, leucine levels and all sorts of other stuff that are, I guess more in the optimization, but you did a great job of just getting some general information out there that everyone listening can put into their life and use. So thank you so much.

Dr. Stuart Phillips: Awesome. My pleasure. It’s an absolute pleasure to be on the show. And again, it’s all about getting the information out. People need to listen to make their own minds up, don’t believe everything you see, and probably from me, as well as the next person and try and figure out what the signal in the noise is. It’s tough, really tough.

Ted Ryce: Yeah, so true. And Stu, I’m going to have your social media accounts up, but is there anywhere else where you’d like to go or have people go to learn more about you or to connect with you?

Dr. Stuart Phillips: Yeah. So for the—I’m told by my sons—the older crowd, I’m on Facebook, apparently, only old people troll around on Facebook, all my sons just coo-coo it but I’m on Facebook, I have my own page. I also have a page with my freedom with the friend limit. But you can easily follow me on Facebook. Easy to find under Stuart Phillips that’s at McMaster University, not the famous hairdresser in London. That’s my alter ego.

Ted Ryce: True.

Dr. Stuart Phillips: I’m on Twitter @mackinprof, I try on Instagram, but I still haven’t mastered the skill. And my kids tell me I should be on Snapchat as well. But I have a Snapchat account, but I am useless at Snapchat. So whatever new social media platform, I’m probably not there. But for the older crowd, I do Facebook, I do Twitter.

Of course, it’s inherently biased, in my opinion. It’s my opinion, but I try to get information out there mainly from our lab. But I also monitor a bunch of other sources. So yeah, follow me on those, no problem at all.

Ted Ryce: Yeah, it’s a source of great information. So definitely follow up on that, if you want to learn the cutting edge of protein research and what you should do. So again, I want to be respectful of your time. But Stu, it was my pleasure and can’t wait until we get you back on the show.

Dr. Stuart Phillips: Absolutely.

Ted Ryce: That wraps up another episode of the Legendary Life podcast. And I hope you learned as much as I did from this episode with Dr. Stuart Phillips. And I want to keep this pretty short because it was a long interview. But I want to just tell you, the reason I have guys on like Dr. Stuart Phillips is because he is the guy doing the research that is providing the evidence as to whether we should believe a claim or not.

And this is so important because I went down that road. I’ve been in this industry for two decades. I went down that road where I used to say a lot of things that I don’t believe anymore. And the reason I don’t believe them is not because I’ve been brainwashed or because something happened that makes me less smart or less critical in my evaluation of fitness and nutrition information.

I’m actually the best I’ve ever been at evaluating the quality and filtering the bad stuff out. And that’s why I love having people like this on because they help us make better decisions. We stopped listening to the people who are like, “Well, protein damages your kidneys.” Okay, how do you know that’s true? How do you know that’s true? What is the evidence that you have that shows that that’s true?

And that’s what you always have to ask. Not just with health and fitness, but with anything, that would be like, hey, I can help you make money. Well show me the people that you’ve helped develop their business into successful businesses. You want to see evidence of things, okay? And you want to see numbers, you want to see data.

And it’s so hard for most people that think like that, because we love thinking with our emotions. We see someone who’s charismatic, and they sound intelligent, and they’re smooth at delivering their ideas and we believe them because the power of their personality. But the thing is: a lot of those people are wrong. And I’ve been down those roads, and I don’t want you to be down those roads, I don’t want you to go down those roads and learn from trial and error like I had to.

We’re at an amazing time in history right now where we can figure things out, for sure. I shouldn’t say for sure, but we are much more clear than we’ve ever been. It is an amazing time to be in this industry right now. And it’s helping us get clear on what really matters, what doesn’t, and what we shouldn’t listen to at all.

That’s my wrap up on this episode. Like I said, I hope you enjoyed, I hope you learned a lot. I hope you have more clarity about protein and the importance of it in your diet. And yeah, that’s all I’ve got to say.

That’s all I’ve got. I hope you enjoyed it. Speak to you soon.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.