I first heard of the rotator cuff 12 years ago when I had a bad shoulder injury. If I had known about this information before I was injured, it might never have happened. As the saying goes, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

The group of muscles collectively know as the rotator cuff is vital to shoulder function. Problems with any of these muscles can cause pain and dysfunction in the shoulder. But exactly what is the “rotator cuff” and what does it do? More importantly, what is the best way to keep it strong and pain-free? These are the questions that this article will address.

Rotator Cuff Anatomy

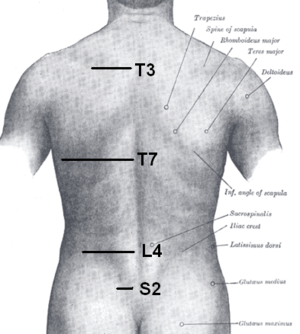

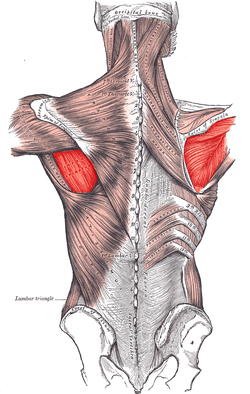

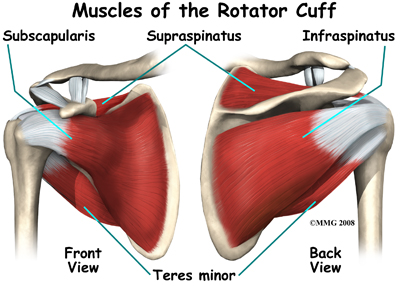

Let’s briefly review the anatomy of the rotator cuff muscles:

The rotator cuff is made up of four different muscles and their tendons. The picture above shows both the front and back view of a right shoulder and the rotator cuff musculature.

1. Supraspinatus. On the back view, you can see the supraspinatus muscle and how it originates from the top of the shoulder blade and inserts into the back of the shoulder bone. It is classified as an abductor of the shoulder, that means it helps raise your arm to the side.

2. Infraspinatus. On the back view, you can see the infraspinatus muscle and how it originates from the back of your shoulder blade to the back of your shoulder bone. It is the second largest rotator cuff muscle and is classified as an external rotator of the shoulder.

3. Teres Minor. On the back view, you can see the teres minor muscle (right below the infraspinatus). It originates from the back of the shoulder blade and inserts on the back of the shoulder bone. It is classified as an external rotator of the shoulder.

4. Subscapularis. On the front view, you can see the subscapularis muscle and how it originates from the front of the shoulder blade and inserts on the front of the shoulder bone. It is the largest rotator cuff muscle and is classified as an internal rotator of the shoulder.

An easy way to remember the name of the muscles is the acronym SITS:

Supraspinatus, Infraspinatus, Teres minor, and Subscapularis.

True Function of the Rotator Cuff

Although you have external rotators muscles and one internal rotator muscle, this is only true from a purely kinesiological perspective. In other words, this is how the muscles work in isolation but not in functional movements such as throwing a baseball or reaching for an object off a high shelf. Actually, all four rotator cuff muscles work whenever you move your arm.

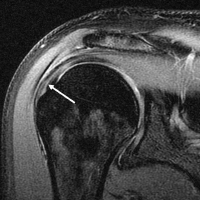

The functional role of the rotator cuff is to provide dynamic stability by pulling the head of the humerus into the glenoid fossa. This simply means that these muscles work together to pull the shoulder bone into the shoulder socket to protect the shoulder joint. Shoulder impingement and rotator cuff tears can result if the muscles of the rotator cuff aren’t working properly or if you have bad mechanics at the shoulder joint.

Rotator Cuff Problems

I’ve got some interesting news for you: you may have or be on your way to having rotator cuff problems and not even know it. In a study by Sher et al., MRIs were taken of 96 asymptomatic (without pain) adults and it was found that 34% of them had rotator cuff tears with 54% of them found in adults over 60 (particpant’s ages were from 19 to over 60 years old).

There are most likely many reasons for this. One important reason was shown by Rathbun et al. where he discovered a part of your rotator cuff (supraspinatus tendon) that has no blood supply. Rothman et al. stated that this area gets larger as we get older and is a normal part of aging. However, this makes injury more likely and decreases your chances for healing.

According to Mike Reinhold, a physical therapist and head athletic trainer for the Boston Red Sox, rotator cuff problems are usually progressive. The progression is as follows:

Irritation–>Inflammation–>Fraying–>Tearing

This means that if you start having rotator cuff problems and don’t fix them with corrective exercise, you might be on your way to tearing your rotator cuff. Solution? Start using rotator cuff exercises in your program. Getting stronger and building endurance is the key here. The stronger you are, the less strength you are using during any activity. Having good endurance will allow the rotator cuff msucles to do their job for longer.

Rotator Cuff Exercises

So you know you should be training your rotator cuff muscles whether you’re injured or not, but what are the best exercises to start with?

Fortunately, some really smart guys did research to answer this question. Reinold et al. did research on 7 different exercises for the rotator cuff and determined that side-lying external rotations had the most for the external rotators. In my opinion, this is the best place to start. However, I believe in doing a variety of exercises as some will work better for you than others so I’m giving you several to try:

Start here with side-lying external rotations:

Standing external rotations are another good option but you need a band or adjustable cable:

Kneeling 90/90 external rotations. The technique for this exercise can be a bit tricky but it’s something you should work up to:

The “W” exercise. I love this exercise! It’s a little difficult for some people to hold the right position throughout the exercise so watch yourself in the mirror to start. Check it out:

Rotator Cuff Program

Here’s what I recommend for a beginning rotator cuff strengtheneing program:

- 1-2 sets of 10-15 repetitions before upper body exercise.

- 1-2 sets of 10-15 repetitions 3-4 times per week

***DO NOT use too much weight or work your rotator cuff until failure!***

If you use too much weight, you’re not working the right muscles. If you overwork your rotator cuff, you cause these muscles to get too tired and they can’t do their job. Keep that in mind!