Are you concerned about your heart health? Well, you are not alone. And the truth is many of us face the risk, especially if we have a family history of heart disease. But it is also true that it can be preventable.

If you’re struggling to understand the information about cardiovascular health, or if you want to find out what an expert recomends for someone with high cholesterol or a history of heart disease, this episode is for you.

In this in interview Ted talks to Dr. Gil Carvalho, a physician and research scientist who is going to reveal important science-based information about cardiovascular health and longevity.

Gil will explore the role of vitamin K2 in removing calcium from the arteries and reducing cardiovascular risk, will reveal the primary cause of arterial problems and will share the type of exercise that can help shrink plaque in arteries.

He will also give some expert advice on how to prevent heart disease, will various methods for quantifying risk factors and assessing arterial health, will talk about the role of supplements, will highlight the need for evidence-based approaches and more. Listen now!

Today’s Guest

Dr. Gil Carvalho

Gil Carvalho, MD PhD is a physician, a research scientist, science communicator, speaker and writer. He is the host of “Nutrition Made Simple”, a YouTube Channel that breaks down the science of healthy eating and provides weekly tips for a healthy diet, always science-based, and always kept simple. His content has been watched by over a quarter-million people.

Connect to Gil Carvalho

You’ll learn:

- Vitamin K2 for plaque reversal

- Calcium score and arterial health

- The primary cause of arterial problems

- Imaging studies for heart health risk assessment

- How to prevent heart disease?

- Lifetime risk and lifestyle changes

- What type of exercise can help shrink plaque in arteries?

- Is there a magic supplement that can help with heart disease?

- And much more…

Related Episodes:

579: VO2 Max Explained: The Key to Longevity and a Healthier Life (And How To Improve It)

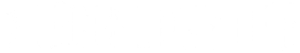

Podcast Transcription: Heart Health Made Simple: How to Reduce Cardiovascular Disease Risk, Boost Longevity, and Optimize Performance, with Gil Carvalho, MD PhD

Ted Ryce: Gil Carvalho, welcome back to the show, man. It's always great to see you and talk to you. Huge fan of your channel.

And it's the channel that, when I get a client who's asking about ApoB and my boring explanation along with one of the screenshots that I took from a study doesn't quite hit home for them, I send them your ApoB video as an example. So really excited to talk with you today and to catch up. Um, so, so yeah, thanks for coming back on.

Gil Carvalho: Yeah, thanks for having me, man. My pleasure.

Ted Ryce: And I wanted to take a different direction because we were just speaking before I hit the record button, and you were talking about a conversation you had with another doctor who also does YouTube and, uh, your channel, which is incredible. And if you're not subscribed to Gil's channel, you got to go to Nutrition Made Simple on YouTube.

I mean, Gil, I think you could and perhaps even should charge for some of the high-quality content, all the time that it takes to do the research, to crunch the data, and to come up with something that's actionable.

And also, another thing that I really like about you, just in case people haven't listened to that first interview that I had you on, is that something I appreciated about you is that I know you're, uh, plant-based, and that's your personal approach, but you do a great job, unlike some other people, um, of separating your personal biases from what the data says.

And I really feel like the world needs more people like that. So, um, if you're listening and you are interested in the data instead of the, you know, tribalism and people only cherry-picking and sharing studies that back up their point, you definitely want to check out Nutrition Made Simple on YouTube.

And then Prevmed Health is the guy who you had a conversation with, and you had a conversation about supplements. Can you talk a little bit about that? What we should know about K2 in particular and how it's relevant to health and heart disease?

Gil Carvalho: Yeah, so it was really interesting, and I think some of my viewers had already asked me to talk to him because it's another channel that's I think about the size of ours, roughly, and talks about cardiovascular disease a lot. He's a cardiologist, Dr. Ford Brewer, so I think I'd seen some comments suggesting talking to him, and then they got in touch with me and said, do you want to come on, we'll do a live show about this topic.

So, I thought that was a really interesting opportunity to talk. And exactly like you were saying, this thing with the tribalism on social media, I think he gets pigeonholed as a low-carb channel. And I probably get pigeonholed as all kinds of different stuff. But the reality is when people who look at the evidence, sit down and go through studies, the agreement on the fundamentals is almost complete.

And I don't think we disagreed on anything fundamental. Anything that we had a slightly different take on, the other would just say, oh, it's because of these studies, and we'd go, oh interesting, okay.

Like there's nothing that's complete opposites, and I think that's the experience pretty much anytime that you sit down with somebody who goes by the evidence regardless of whether they prefer lower carb or higher carb or lower fat or higher fat, those are personal preferences but um the science on the pillars is, there's widespread agreement.

So today we focused on vitamin K and specifically vitamin K2 and cardiovascular disease because it's a very common question and basically, the background without getting too nerdy vitamin K can be obtained from a number of food sources and there's different kinds, there's two main kinds, K1 and K2 and K1 is mainly from vegetable sources and K2 mainly from animal sources although there are also some fermented foods that can be like for example natto from Japan is very high in K2 because the bacteria can produce K2 as well, they can convert K1 into K2. So there's a question about vitamin K and calcium in your arteries.

So, you might have heard about the calcium score and all the calcification in your coronary arteries and all this world. And so, there's a very common question about vitamin K's action in removing calcium from the arteries and reducing cardiovascular risk and all this stuff.

And so basically, we did this one-hour live show where we went through a number of recent trials, randomized trials, some as recent as this year just came out, actually like the last couple of months, looking at exactly this question of supplementation with vitamin K and then calcium progression and cardiovascular risk.

The bottom line is that there's a lot of heterogeneity in the studies...

Ted Ryce: When you say that, what do you mean? Yeah. Can you explain that?

Gil Carvalho: Yeah, meaning that you tend to see results that seem to conflict. So, in one study they might see a reduction in the rate of calcium progression and in others they might not see anything significant and part of that, so as we were going through the studies, part of that is the way these studies are designed, the dosage of the supplements and the kind of the time that you follow these patients for what's called the follow-up, that tends to vary a lot from trial to trial so that could be part of the explanation for why you get these different findings.

And then one of the main takeaways that we had and this was interesting because going into it we knew the topic that we were going to talk about and we had exchanged studies beforehand so they sent me a number of studies that they wanted to cover and I sent them one or two that had just come out that I thought was interesting also to touch on. But we never had a conversation about what our points of view were on the whole question, but we actually had the exact same general take which is that the focus on calcium can sometimes be misleading, the focus, this focus on the calcium the calcium calcification and trying to take calcium out of the arteries can be kind of a distraction.

The reason for that is that this calcium score measures the calcification in your arteries and that's essentially a readout of how much plaque there is in your arteries, and how long plaque has been growing for because calcium is a is a pretty late event in calcium in a black progression.

So, when you first start accumulating plaque at whatever age, plaque starts growing, depends on the individual, but it could be at 30 or 40 or 50. In the first few years, you don't see calcification. It normally takes years to even decades to see calcium. It only pops up later on.

So, when you do this calcium score, and you see somebody who has a very high calcium quantification in these Agatston units, it's an indicator of how much plaque is present.

One analogy is that it's like the tip of the iceberg, right? If you see it, it indicates that there's a lot of ice below the surface – calcium is sort of like that. But the misconception is that it's calcium itself that's the problem, and so we want to get rid of the calcium from our arteries. That's the goal.

That's a misconception. The calcium itself doesn't cause the problems. In fact, there's plenty of evidence that the calcium might actually be part of the regeneration of the artery, part of the repair of the artery after injury, and also some evidence that in some contexts where you see people's calcium go up, risk might actually be coming down – risk of a heart attack and an actual event.

So, it's a little bit confusing because yes, if you go to the doctor, especially if you're young, if you're 40 and you go to the doctor and you have a high calcium score, yes, that has prognostic value, and that does suggest concern. It does suggest that things need to be managed better.

Not because that calcium that's there causes the harm, but because it's telling you that you have a lot of plaque. A lot of plaque that has been growing for probably decades. That's the reason. And actually, the most fragile or the most vulnerable plaque – the most likely to rupture and cause an event – is actually the soft plaque that is not picked up by the calcium score but is almost certainly there when you have detectable calcium.

So, I hope that makes sense, and let me know if it's confusing, but that's kind of what we were getting at, trying to clarify this idea and why the strict focus on getting rid of calcium might be myopic.

Ted Ryce: Yeah. And so, just so I understand correctly, what you ended up starting with was talking about vitamin K2 because it can help prevent or even maybe remove the calcium from the arteries.

But then it led to this whole conversation about we're really talking about the wrong thing here because the calcium buildup is actually, or at least there's some evidence showing that the calcium is there to help regenerate the damage from an artery. I mean, what popped up in my head is someone has high blood pressure, that pressure creates some damage. Maybe there's some calcification happening to reinforce the strength of the wall as an example; that's an example that, uh, Robert Sapolsky gave in his book, uh, "Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers," and always stuck with me.

And even if you do have a higher calcium score, by the way, had a client recently, had a high calcium score, and it was interesting, the cardiologist's reaction to it. And what I hear you saying is like, yeah, um, it's a marker of like, "Hey, he's in his fifties." So, to your point, that's something you want to pay attention to. But the issue with the calcium score is the soft plaques aren't quantified.

So those are the ones that are more problematic because the calcium doesn't break off as easily as the softer plaques and create heart attacks and strokes. It brings. I was starting; I wanted to start with this conversation about supplements, but I feel like we're going down a much, and I wouldn't mind coming back to supplements, but I feel like we're going down a more important road here where it's like, "Well, what are the tests that we need to be doing? If the calcium score shares some important information, but also like you've talked about on Twitter and in your videos, a calcium score of zero doesn't mean you're in the clear.

There's a significant number of people or a significant percentage of people that have heart attacks and other things that had a calcium score of zero. And then even if you have the calcium buildup like we just talked about, the soft plaque isn't quantified. So, if you were someone who is super concerned about heart disease, what would be the best way to quantify your risk with the technology available right now?

Gil Carvalho: Yeah, I mean there are different levels, right? So, you can quantify your risk long term by looking at your metabolic and blood work in general, like your blood work parameters. That gives you an estimate, at least at a population level, of risk long term. In terms of looking at your actual risk, for example, you can do imaging studies.

Something that we talked about in this live show is called the CIMT (carotid intima medial thickness) assay, so it measures. It's a readout of plaque in the carotid arteries of the neck, so it actually can pick up changes in soft plaque as opposed to just calcium, so that's one way.

There are other ways to look at coronaries as well, something called the CTA that shows more soft plaque than the calcium score. So those are things to detect, to sort of get a sense of how much plaque you already have.

And then in terms of risk factors, these are things that you want to manage – what we call kind of primary prevention or even primordial prevention is what you want to prevent the problem in the first place before it even arises, before you even have the plaque, and that's things like I mean the risk factors that you've heard about all your life, keeping your glucose in the healthy range, your blood pressure in the healthy range, your BMI or your body fatness in the healthy range, your inflammation, your cholesterol/ApoB – all of these things are going to help you minimize your risk long term.

Ted Ryce: Yeah, and right, so it's funny, those things that you just talked about, the things that we've heard about, I feel like a lot of people don't really take those that seriously, at least from the people that I end up working with, and it's like, man, your cholesterol's high, right?

Because I look at my clients' blood work, I don't make, you know, I don't diagnose or treat issues, but we can at least say, "Okay, well, if we make changes to your diet, does that do anything?"

And yeah, and I see a lot of high cholesterol. And I also have clients who want to take the next level, and they want to be even more proactive. So, doing those two tasks now, the CT, the CTA, uh ...

Gil Carvalho: A CTA is an angiography, so you do have to have a contrast injected into. The other one is less invasive, the CIMT. CIMT you'll find it; if you google it, you'll find a CIMT, and if you need to specify carotid, you'll find it. So that's an ultrasound of the carotid arteries. You don't need to have anything injected ...

Ted Ryce: Right. So, the other her one's a bit more of a, like the radioactive dye there there's more risk is what I'm getting from what you're saying.

Gil Carvalho: There's a little bit of radiation exposure. So again, it depends. You wouldn't do this yearly in a young healthy person just for kicks. But depending on the individual, it might, you know, the risk-benefit might be worth it.

So that's more of a case-by-case consideration. But the CIMT is, I think, an interesting thing to discuss with your doctor, with your cardiologist since it's not invasive.

Yeah, these things can give you a sense of whether you have plaque growing or not. And in cases where people are unsure or maybe borderline cases, they can help you kind of, you know, tilt one way or the other.

Ted Ryce: Yeah, and to follow up on that a little bit, you said the right thing, like, bring this up to your doctor. Very interesting, though. My client, this is kind of a fascinating, hopefully you find this as fascinating as me. But my client worked with me for a year, lost, lost 56 pounds.

And when he showed up to a new doctor, his new primary, he was like, "Hey, listen, and he has a history of heart disease. So, his dad died from heart disease. He said, listen, I'm interested in, you know, looking into my heart disease risk because he hadn't been to the doctor in years; I got him to go and said, you know, it's not just working out, losing weight, you got to get a checkup. And so, he went the doctor based on how he was presenting.

He's like, "You're low risk. Your weight is good. Your cholesterol, all these, the blood work is good," but his previous blood work wasn't, and he had just lost 56 pounds. And the first step was to get a calcium score.

That's what the next level, that's what the doctor told him, the next level, but he really didn't think it was good to get because you just don't have enough risk factors to warrant it.

But my client pushed and said, "I want it because I have a history and I just lost a bunch of weight." So, as you mentioned earlier, Gil, it takes decades for heart disease to build up. He's been out of shape for a long time, just got into shape in one year. As much as, as great as that is, it doesn't negate all the buildup from the previous years. He's been overdoing things.

So, he ended up getting the calcium score. I forget exactly what it was, but it was quite high. And then it's like, well, and then he ended up going to the cardiologist. The cardiologist didn't recommend yet going and getting some testing.

Now, I know you're not a cardiologist, Gil, even though you're a bad-ass doctor and you have a PhD. But like, I mean, if you were in that situation, what would you personally push for?

I know I'm not giving you a ton of data here. I don't remember exactly his calcium score, but if you were in that situation where like your calcium score was on the higher side and you had a history of heart disease and, um, you're in this situation, what, and you're already taking care of like the lifestyle components, you know, what would you do?

Gil Carvalho: So, the first thing to say is when somebody has a high calcium score, you automatically have indication for lipid-lowering treatment and especially with a family history so right off the bat because of a healthy cholesterol for someone without those risk factors it might be too high for somebody in that situation. So, it's indicated to have their ApoB slammed lower with the treatment.

So that's one thing. Another thing that comes to mind, and this is not applicable to everyone, but in someone with a family history, it's definitely something that I would measure, and that's something called LP little A. I don't know if you've heard about that. So, it's a type of lipoprotein. It's in the LDL family. It's a subset of LDL lipoproteins.

And this is something that is elevated in about 20% of people. So, one out of five, it's not going to be everybody, but it's certainly not rare. One out of five people has this elevated.

And this is a cause of what's called residual risk. Once you've addressed all the classical risk factors, some people and some families, you still see, quote unquote, unexplained heart attacks. And some of those are explained by this Lp(a), so that's a blood test you can, just like you can order an ApoB, or, you know, your LDL cholesterol, you can order your Lp(a).

Ted Ryce: Yeah, got that.

Gil Carvalho: And so that's something that's gotten more and more attention lately in the cardiology world, and for somebody who, actually what's indicated now is for everyone to measure it once in their life because most of the determinants are genetic.

So, if you measure it once and your LP little a is good chances are you're okay the concern is much diminished for the rest of your life.

But it's indicated that everybody measures it at least once to rule it out. And yeah, in a case like this, a family with history, it's something that I think makes sense to look at. And then the other thing is exactly what you said. He got in shape recently, but he has a lifetime of risk factor exposure.

So, it might just be that all of those years of obesity and prediabetes or insulin resistance. Again, we'd have to look at the specifics of his case. Right. But all of this, maybe the blood pressure wasn't ideal. Maybe the cholesterol was too high. ApoB was probably too high. All of this over 40, 50 years in someone who has the susceptibility led to plaque accrual. That's the usual story. And now he got in shape.

That's good. That's going to diminish the risk from where it was, but and this is a good realization is we don't by addressing risk factors, you know, it's better late than never; he is certainly at lower risk almost certainly depending on the specifics but almost certainly at lower risk now than he was a year ago, but it doesn't mean that you magically undo 50 years of damage. So that's something that needs to be always considered, and that's good that he's on top of it now.

Ted Ryce: Yeah. Um, I wanted to bring that up in part because I was curious about your answer and because one of the things that I learned from you, actually, I think it was more from following you on Twitter, you've talked about the lifetime risk, uh, the lifetime exposure risk.

And it's something that I don't think is in the conversation about getting healthy enough. So, everybody is like, "Hey, I'm just putting off my health, but you know, I lost weight before I can start an exercise program and get back into it and now, I'm in shape. You see, like...

It's not exactly like that with heart disease, at least maybe with other, um, medical issues, I don't know, not my wheelhouse, but with heart disease in particular, it's like that, that risk doesn't, it changes for sure. But if you have that buildup already it's not like you're just going backward and removing all the risk. You're still going to have some issues.

And if you, and I'm just thinking for myself, if I had, I don't have, you know, my dad died of other things. He was said to have had some plaque buildup, don't know the extent of it, but he never had a heart attack, right?

But if I did have a history of it, I'd be on top of this more. So just understand if you're listening right now, yes, you can get in shape at any age. Age doesn't stop you. There's no magic switch.

You can be in your 80s. Most of us won't even live that long, at least according to the data on life expectancy for Americans. But if you do, you can still lose fat. You can gain muscle, right? But this other stuff, that's a different story altogether. Anything, any follow up on that? Anything you want to add there?

Gil Carvalho: Yeah, I mean, I don't want to discourage people or, you know, disappoint people if you are 50 or 60 or 80 and you have a lifetime of exposure to risk. Look, we don't have a time machine, but yes, if you make changes now, yes, they will make a difference.

And there are things that can reduce risk substantially and we have some recent videos looking at some reduction in the plaque size with exercise it's also been shown with lipid lowering treatments.

So there are things that can substantially improve things what I'm trying to emphasize and I think that you were trying to do the same thing is the potential right the bang for your buck is really going to come from starting early before the disease is set and doing this long term and passing this message on to people. I just recently had the opportunity.

They invited me to talk to a high school class in the UK. And at first I was like, I'm not used to talking to teenagers. Like, I don't want to put these kids to sleep, right? Because normally my audience is like 40, 50 or beyond.

But what I realize is that this is actually when you want to impart some of these principles because this is when people have the power to really change their lives is preventing the problem in the first place.

So yeah, I mean the basically I guess that my message is start today. You can't change the past but, don't put it off thinking that you're going to have a magic bullet in 20 years.

Ted Ryce: Yeah. Great reminder. And Gil, you know, to stay on the heart disease, of course, it's about to exercise and actually, you know what, let's dive into that cause I watched that video, uh, I thought it was really cool because one of the first things when I started following you and some other people, you know, I need it, my cholesterol is good and, but I'm curious, like I want to get my calcium score done.

And, you know, in that age range where you start to like, I want to get ahead on, uh, get ahead of this. But one of the things that I Google was, can you reverse plaque buildup?

So can you talk a little bit about that idea and also about the video that you recorded on this and just in case you want to go watch it, the name of the video on Gil's channel is called “This Exercise Shrinks Plaque in Your Arteries”.

So, it's right. If you go there, it'll be in the top, you know, let's say eight, depending on when this goes out.

Can you talk a little bit about the idea of shrinking plaque and what the studies found?

Gil Carvalho: Yeah, so this was a really interesting trial. And it was looking at exercise, specifically, was HIIT, or HIIT, or however people call that. So, I imagine most of your audience is familiar with that, but you basically intersperse periods of high activity exercise with some rest periods. And so, they put people through that. I forget exactly how long. I think it was like a couple of months, six months, I think.

And they did see a significant reduction in plaque thickness in the group that was randomized so this was randomized only half of the people had that were assigned to that exercise program. The rest received what's called the standard of care so you know the normal advice, you know, eat healthy, exercise, all these types of things, but they didn't get this structured program with would HIIT and these trainers going in and supervising.

And this was twice a week and it was fairly intense and then they were encouraged to do more of that exercise at home. So bottom line they saw a statistically significant reduction in the plaque size over the six months.

Caveat: The change is very small, about 1% of the artery lumen. So, they went from, I think it was 49%. The way they did it is they measured the largest lesion, the largest area of plaque, and it covered about 49% of their arteries.

So, these are people who have substantial atherosclerosis already, right? These are not super healthy 21-year-olds.

So, they had about 49-ish percent of the artery blocked in this largest lesion, and it went down to about 48 percent blockage, so that sounds like a very small reduction that's 1% of the artery lumen that got unclogged and about 2% of the plaque that got reduced.

On the other hand, we have a lot of evidence from trials looking at medication that indicates that a one percent reduction in plaque size correlates with about a 20 percent reduction in risk over a number of years.

So, I wouldn't discard a one percent reduction. It could be meaningful in terms of risk reduction although this trial it's very important to mention this trial just looked at plaque measurements; they didn't actually measure events, they didn't measure heart attacks and strokes or anything like that because for that, you need a longer time and more people, but it does suggest that exercise can help with some level of reduction.

But again, notice that it's something that's relatively modest; it's not, okay, I cleaned up my lifestyle and suddenly everything, the plaque just magically disappears.

And we don't know if we prolong that six month into the future. We don't know if it's a linear thing and you get a reduction of another 1% every six months or if it plateaus; it's impossible to say at this point. But yeah, it kind of aligns with what we were saying. Yes, these things can help. They're meaningful. Absolutely do them. But if somebody tells you that it undoes decades of bad behavior, that's a bit of an overstatement.

Ted Ryce: Got it. So, we can shrink the plaque and can you talk about, you know, with in terms of the plaque reduction in our conversation, a few minutes ago, you talked about the calcification and the soft plaque was the reduction in plaque? Was it the soft plaque? Was it the calcium? Did they get into those details?

Gil Carvalho: Total yeah right, it's an actual measurement of plaque so it's not just calcium. That's a good question, so they're not just looking at calcium score which would be less interpretable they're actually looking at measuring the plaque thickness, the total plaque thickness, and that got reduced. So, it is more meaningful than a calcium reduction.

Another thing that's interesting to point out, and this is something that also sometimes causes confusion. Like we were saying, when people have a high calcium score, they have indication for lipid lowering treatment for medication, whether it's a statin or another class of medication.

And what we've seen with several datasets is that this treatment can actually increase the calcium score. The calcification goes up. So, a lot of times that throws people off because they say, well, doctor, you put me on the statin and my calcium got up higher so it's worse for me.

But the risk comes down in these randomized trials; we see fewer heart attacks and fewer strokes, and the thought is that precisely this calcium is some stabilization of the existing plaque.

And so, another example of this disconnect between the calcium number and risk per se, which at the end of the day is what we care about.

Ted Ryce: It's a really good conversation. It reminds me, I had the, do you know Mark Haub, the Twinkie Diet, the professor in the Twinkie Diet and all that? I had him on the show not too long ago to talk about it, and to talk about it in more detail. But one of the things that came up about nutrition is that it's very nuanced. And people don't like nuance in general, or at least on social media, let's say.

Hopefully, this audience appreciates all the nuance that we get into, or they wouldn't be coming back, I guess. But, you know, it's very nuanced, like you said.

So, calcium score, and this is why it's important to talk to people like you and to listen to people like you and the other health influencers with a solid evidence-based perspective on this or data-driven perspective because it's like, well, you take a statin, and I know the arguments rage on social media about statins and what they do, and it's not that controversial, but it's controversial on social media at least.

And then people will say things like, yeah, well, your calcium score will go up. And here's, here's some data showing that when the actual important thing is, well, what happens to a human being when they take it? Does there, do they have fewer heart attacks? Yes or no, because that's what really matters.

And so we have to take in all this information and then at the end of the day, say, "Okay, well, what does this really mean for what might happen to me or in terms of like, you know, heart attacks or strokes?"

It's a bit, I'd say that because if anyone's just trying to, you know, follow along and maybe they don't have, they haven't watched as much of your channel because I don't dive into this level of detail. And nor do I know enough to dive into this level of detail with heart disease, you got to pay attention to those nuances.

Gil, you already mentioned the big ones and you mentioned, right, lose the excess fat, get into better cardiovascular shape.

I had Brady Holmer on as well not too long ago talking about VO2 max, that's another, that's something that you can do to improve your, yeah, to increase your health span or potentially your longevity.

To return to that initial conversation about supplements though, people are so gung-ho on supplements. If you want to get rich, you know, I, here's what I'll say it like this. I think I could start a supplement company, tell people, "Don't buy supplements. You're wasting your money, even though they're good. But the supplements I'm selling are good.

And let's say I'm selling evidence-based supplements than supplement formulations, but there are only 5% of what's going to give you results. Please don't buy them. But if you're going to buy and buy them for me, here's the link to my website," I bet you I'd be an eight-figure business owner.

But just because people love supplements so much. There's this, I don't know where maybe it's, you know, this idea that we take a pill, everybody wants a pill to do something magic.

So, make sure you focus on the other stuff. However, in that last, let's say everybody's got stuff dialed in.

What other, like, we didn't finish the conversation about K2 in the sense that is it something beneficial? What about CoQ10 or some other supplements with heart health? And let's talk specifically about the cholesterol thing. And what have you found or found out there about supplements or what can you share about that?

Gil Carvalho: Yeah, my take on supplements is the same as my take on anything else, as long as there's evidence for their benefit. I'm open to it. And if there's no evidence, I don't oppose them on principle. But I think a lot of times, the supplements are hawked based on a hypothesis or what we call a mechanistic speculation.

This is like when people say, "Well, this substance increases the level of this and phosphorylates this other thing so you definitely want to take it," and that's not how we draw conclusions in medicine; you have to actually show the benefit in human beings taking the supplement or the drug.

So, in general, I think supplements have a place if there's, for example, a nutrient that you're deficient in, that's a place where a supplement can top up something that you're missing.

Another situation would be a nutrient that you're not getting enough of from your diet for whatever reason, somebody who has an intolerance and can't eat certain foods or has a restricted diet for some reason.

Sometimes in an elderly population, there are appetite issues, there are absorption issues, and so I think it has a place to sort of fill in those gaps.

In terms of cardiovascular disease, I don't know if there's a supplement that I've seen compelling evidence that everybody needs to take. I don't think so. There's nothing that I would recommend universally.

The story with K2 that we were covering today is pretty to be confirmed in my view. Like there's a lot of these trials that find a reduction in the calcium accumulation in some patients, but not others. The outcomes are unclear.

I would not, based on the evidence we have, I would not tell everybody to go buy vitamin K for cardiovascular purposes. But I wouldn't, I'm not against it. Like if studies in the future show benefit in actual events, then I'll be an advocate. I just haven't seen that evidence.

And I think a lot of the social media content tends to jump the gun and kind of go on theory or sometimes a study that's not that compelling and the problem with that is well there's several problems with that one is that you risk sending the person in the wrong direction, could potentially cause harm or could just distract people from things that actually work and have been and have more evidence behind them.

And the other problem is just kind of the argument being clunky like confusing people with evidence that isn't most compelling. I don't know if that was a confusing answer but those are our general thoughts.

Ted Ryce: Yeah, well, you're saying, well, there's no there's no magic supplement that's going to help with heart disease. And a lot of what's out there gets hyped up on social media. You know, people, people point out to point like, oh, well, there's financial gain.

And obviously, for sure, in many cases, some cases, many cases, there's that. I also think even more potentially or at least more concerning for me are the true believers, you know, the people who are just like, they're so, they're not, I think you can eventually figure out like Liver King was not actually just super jacked because he ate raw liver, he was taking steroids.

But then the true believers who are so obsessive about some things. It's a bit more concerning. I think, or at least in my case, maybe I'm just more concerned about I'm like, man, this guy really believes in this.

And, you know, people make a great argument and they can be sincere, but sincerely wrong with their interpretation of the evidence and again, it just leads to wasting time and not getting results or like you said, you're not taking action on the most bang for your buck methods, because you're trying to figure out, well, should it, should it be K one or K two or what's the optimal, um, maybe it's both, but what's like the optimal ratio of K one, K two, you know.

So that's what kind of come, uh, what I got from your explanation, your answer.

Gil Carvalho: Yeah, one thing, so you touched on two interesting things there. One is this idea of conviction and kind of personal belief. And one thing that we have, this is why it's so important that views in science be backed up by evidence. Not just supplements, but I think in supplements that might be even more pervasive because we have this placebo effect that is so well characterized and so common.

And so, not to mention other variables in our lives, right? So, we might start taking a supplement and we also, whatever, started eating a little cleaner and started exercising a little bit more, and we start seeing improvements and maybe has nothing to do with the supplement and also there's a placebo effect; we just started taking a supplement that we really believe in, and we just feel stronger and we start performing better.

I mean, this is why in science you want to see robust evidence; you want to see, ideally when we're talking about supplements and medication, you want to see randomized trials with a placebo control group so that you can satisfy yourself that these trivial explanations are out of the picture. So, I mean some of the common things you'll see are testimonials on the internet when somebody says, "Yeah, I'm selling this supplement. I don't have any evidence for it, but here are all the testimonials”, that's worth next to nothing scientifically.

I don't want to be dismissive, but that's the truth.

Ted Ryce: with a supplement in particular.

Gil Carvalho: Yeah, if people are putting their testimonials front and center, what that tells me is that they don't have scientific evidence to show. But I also understand because the testimonials are more compelling for the majority of people; what they want to see is they want to hear another human being report that they felt better, right?

The bar graphs and p-values don't impress most people. So, I get that. But I'm just trying to familiarize people with this other world where testimonials are very low-level evidence.

The other thing you touched on is the financial interests. I think that's a reasonable concern. The thing I would point to is that there's financial concerns behind everything.

Behind pharma, behind supplements. Supplements are also a multi-billion-dollar industry, so nobody is making supplements and selling them for charity. You know, behind every food that you can imagine there's a financial interest, so I mean, if we're going to discard things because of financial interests we have to be consistent and discard everything and everyone alive has a bias. So that's not really informative, I think.

What is informative is reproducibility in science. That's how we figure out if something is likely to be real. If a study points to benefits of a supplement or a drug, you want to see it repeated, you want to see it done by different people,

different institutions, different setups in different populations, and that's when the confidence goes up.

So, that takes care of a lot of these concerns that they cooked the books or something weird about that study, because when you see the same thing, done by 10 different universities, 10 different investigators, the likelihood that all of them are complete crooks that just made up the results, starts to be next to zero.

So that's essentially how we figure out in science what's likely to be true. And the confidence goes up and up as you see reproducibility and vice versa. If you don't have reproducibility, the confidence never goes up or goes down.

So yeah, I think the concern with funding and money and follow the money is very understandable, especially because people don't have a direct exposure to the science and a lot of times, they're just kind of given this message of trust the scientists, trust the experts and that's also not fair and not it's kind of infantilizing people, just yeah, just do what I tell you and, you know, don't worry about it, don't worry, your pretty little head, I'll take care of the, you know, just do what I tell you.

It's not really the way to communicate science. But so, I get it. People are hearing these dictates do this, do that. And then and then they're seeing all these scandals and all this money exchanging hands and all these problems arising. I'm not shocked that there's enormous distrust.

Ted Ryce: Do you think it's going to get better?

Gil Carvalho: It's an institutional problem, right? Anytime you have..., these industries are all, their primary motive is profit. So, none of them are there for charity, whether it's, you know, whatever, the beef industry, the dairy industry, the alternative meats or alternative dairy, the pharma, the supplements, it's all the same problem. They're there to make their shareholders happy and increase the value of their shares.

So, there's always going to be cutting corners and this is always going to be a thing. Now, again, I think science, we can't... First of all, science isn't based on trust. So, this is something that I like to say in my videos.

Trust is for friends and family. It's not for strangers on the Internet, and it's not for scientific studies. We don't really base it on trust, we scrutinize things, we go over methodology, and then we look at reproducibility, what we already touched on, right? So, this is the opposite of trust.

Trust would be, you know, an expert tells me X, then X must be true. That's not really how it works. Anyone needs, everyone needs to back up their statements with evidence, even the top experts. So yeah, I think it's a process of diminishing uncertainty. That's how I like to see it.

And this makes people uncomfortable sometimes because we like things to be black and white. We like things to be 100% or zero. Tell me yes or no. But the reality of the world is that, it's a world of navigating uncertainty and making educated decisions with the best information we can get.

And I think science is one of the best tools we have for that purpose where it stacks the deck in our advantage. It doesn't guarantee that we win every bet. Nothing does. But there's nothing that I know that can help us and stand in our corner like looking at the science in a broad sense can.

Ted Ryce: Powerfully stated, Gil. Yeah. I don't know if you remember my story, but I was a convert from down in the low carb trenches and the paleo before it was paleo, believing in insulin as the main driver in carbs and the insulin response is the main driver of obesity, having nothing to do with calories and then, you know, finally making it here.

So, and, and I think a part of that comes from, I met you more recently, but when I was struggling to lose fat, found guys like Alan Aragon, Spencer Nadolsky and Lane Norton, actually Spencer, I think I've learned about later, but Lane Norton is another one. And, and I started getting results.

And I started cutting down on the things that I was worried about, concerned about, and that helped shift me to where I'm now, where I'm trying to be, I'm trying to follow in their footsteps and give people more access to people like you who are more data driven in their approach, less tribally oriented about, you know, toting the nutrition party line and really, you know, diving into the data and the nuance and having those tougher conversations.

So really appreciate what you do. And, um, yeah, always a pleasure to talk. I know it's coming up on our time here.

If you're listening now and you want to hear more about heart disease, about some of the other topics that Gil covers, you've got to go to Nutrition Made Simple on YouTube.

It's again, when I have a client and they have high apolipoprotein B levels or cholesterol, I send them a video of Gil. And Gil does a great job of not just explaining it, but your thumbnails are eye-catching, and you do a great job making it entertaining.

And it's no wonder that you have over 200,000 subscribers now. You just do a great job at helping people ride that line between, you know, being open-minded enough.

Like what you said, it's not just about listening experts and following blindly what they say. It's not how science works either, but also not falling prey to the myriad claims that random health influencers on the internet make.

So, I really appreciate you, appreciate your time, and anywhere else you want people to go to connect with you?

Gil Carvalho: Oh, they're welcome to link up on Twitter. Handle is @nutritionmades3. That's the two main places I hang out at right now. I'm starting to think about going into TikTok and Instagram. But right now, the main ones are, YouTube is the main hub and then Twitter sometimes.

Ted Ryce: You got it. Well, like I said, really appreciate you appreciate what you do. And thanks again for coming back on the show and sharing your wisdom and your knowledge with us.

Gil Carvalho: Thanks for having me. Take care.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.