by Ted Ryce

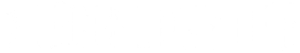

521: Do Hard Things: Debunking Myths and Misconceptions about Resilience and Real Toughness with Steve Magness

by Ted Ryce

by Ted Ryce

521: Do Hard Things: Debunking Myths and Misconceptions about Resilience and Real Toughness with Steve Magness

521: Do Hard Things: Debunking Myths and Misconceptions about Resilience and Real Toughness with Steve Magness

more

by Ted Ryce

521: Do Hard Things: Debunking Myths and Misconceptions about Resilience and Real Toughness with Steve Magness

It would be fair to say that almost all of us, at some point in our fat loss journey, submitted ourselves to crazy workout routines, highly restrictive diets, or extreme habits. Perhaps for short periods, 30, 60, or 90 days.

If we look at it from the perspective of short-term goals, it kind of makes sense. It’s achievable, and we can see the finish line relatively close; it motivates us. We believe that if we are tough enough and have enough resiliency, it’ll work as long as we commit to those short periods.

It can even work perfectly fine; we can even see some results, but… what happens after that? Is that model sustainable? It is a proven method for short-term goals, but what about the long term?

So, what is the best use of our resiliency and mental and physical toughness?

In this episode, Ted chats with the world-renowned expert on performance, author, and executive and performance coach for NBA teams, Steve Magness, about the true meaning of being resilient and developing real toughness.

He shares 4 powerful tips to help us commit to long-term goals, the importance of creating an emotional attachment to rely on while pursuing our objectives, and how crucial it is to get support as we do it.

Plus, he explains how poor stress management is a recipe for defeat, the importance of positive reinforcement in leadership, and shares an inspiring story from his book.

Steve also explains why he believes that although there’s a lot we can learn from the military, we took the wrong lessons from them and much more. Listen now!

Today’s Guest

Steve Magness

Steve Magness is a world-renowned expert on performance. He is the author of the new book “Do Hard Things: Why We Get Resilience Wrong and The Surprising Science of Real Toughness”. He is also the coauthor of “Peak Performance. The Passion Paradox”, and the author of “The Science of Running”. His books have sold more than a quarter-million copies in print, ebook, and audio formats.

Steve has served as an executive coach to individuals in a variety of sectors. His work serves on applying the principles of which he writes. In addition, he’s served as a consultant on mental skills development for professional sports teams, including some of the top teams in the NBA.

Connect to Steve Magness

Book: Steve Magness – Do Hard Things: Why We Get Resilience Wrong and the Surprising Science of Real Toughness

You’ll learn:

- Why do we have a misconception about what is hard in life

- The importance of planning our habits and routines with the long-term horizon in our minds

- Why is it so hard to stay motivated in the long-term

- Four ways to set ourselves for success in the long-term

- The most effective way to manage stress

- What is fake toughness and, therefore, what is true strength

- Dealing with our own bias and the narrative in our heads is actually the most challenging part of staying committed

- The most challenging part of staying committed and how to overcome it

- What are the things we can do to create resilience

- And much more…

Related Episodes:

254: How To Achieve Peak Mental Performance with Dr. Chris Friesen

332: The Power Of Resilience with Tom Heffner

Links Mentioned:

Watch our Body Breakthrough Masterclass

Do You Need Help Creating A Lean Energetic Body And Still Enjoy Life?

We help successful entrepreneurs, executives, and other high-performers burn fat, transform their bodies, and grow successful businesses while enjoying their social life, vacations, and lifestyle.

If you’re ready to have the body you deserve, look and feel younger, and say goodbye to time-consuming workouts and crazy diets, we can help you.

Go to legendarylifeprogram.com/free to watch my FREE Body Breakthrough Masterclass.

Podcast Transcription: Do Hard Things: Debunking Myths and Misconceptions about Resilience and Real Toughness with Steve Magness

Ted Ryce: Steve Magness, thanks so much for being on the show today. I’m really excited to dive into this topic about Doing Hard Things. But I think before we get into that, let's add some context. And if you could share your superhero origin story, if you will, how you got started and how you got into talking about this concept?

Steve Magness: Yeah, absolutely. So, I think it goes back a really long ways for me, which is, you know, I've always been an athlete and a sports fan. And growing up, I played every sport, basketball, baseball, soccer, all of them. But I ended up being really good at the one sport that I honestly didn't like very much at the beginning, which was running and track and field.

And I grew to love the sport. But if you know anything about running, and I was a middle-distance runner who ran the mile, is, it is literally you alone in your head, navigating discomfort, pain, fatigue, like feeling and experiencing and having these negative voices that are telling you to quit, to stop, to slow down. And you got to figure out how to get on the other side of them and continue onwards.

So from a very early point, like I was used to, okay, what does it mean to “be tough.” And as I think as I moved on from my athletic career, and got into life, I realized quickly that, you know, well, it might not be the physical pain or discomfort, we're all kind of faced with these challenges that put us in that same spot, where our brains kind of telling us like, escape, like, avoid, don't do this, and we have to figure out how to get on the other side of it.

And in terms of getting to this book, what happens is we tend to write the books that have meaning towards us that we're struggling with. So in my own life, I came back to this own experience of like, okay, well, what does it mean to, you know, take on hard things, or difficult challenges and navigate them? And is there a better way to do it? So, it was highly relevant to me.

Ted Ryce: Can you share a little bit about that? Because like we talked about before, we press the record, there's a misconception about what's hard. People do things. And they're like, and I'll give the example from my field, the 75 Hard workout twice a day. Do you know what that is? By the way? Have you ever heard of that?

Steve Magness: No, I don't.

Ted Ryce: Oh, man, you'd would love it. So it's 75 days, two workouts per day one needs to be outside, you need to follow a diet, no cheating, or else, you have to start the whole thing over again, you’ve got to read 10 pages of a book and post a selfie, a gym selfie. And there's a group of entrepreneurs who love it.

But you see, I, through the years, have just watched people on social media, “I'm doing this 75 Hard again.” And then, “Oh, I had to quit, I cheated on my diet” It's like, “Dude, that's not the hard thing.” It's like, you're really comfortable with this extreme doing nothing, and then going extreme and then doing nothing.

And even if you complete it, you know, and it's just like, that's not the hard thing, buddy. The hard thing is really to figure out, how can I do this for the rest of my life? How can I be fit for the rest of my life? So, I'm going to try to contain myself here, because I have a lot of personal stories about it. What's that?

Steve Magness: No, I was going to say, keep going. I love it. I mean, I love it, because it gets at the central part of the theme that I was noticing, too, is that we often— it's not that we don't give effort, we're often doing difficult things. But what happens is we give effort to things that don't really matter, or don't really make a difference in the long run.

So that example there, and I am going to take us down this tangent because it's perfect and encapsulate stuff, is that like the athlete who goes and posts their crazy workout on Instagram, and says, like, “Look at this thing I did. I went until like, threw up,” what have you.

But then the next day and the next week and the next month, and then for the rest of their career. They're not like doing the consistent work that actually leads to gains. And I think what you're getting at with this 75 Hard, is it's like, whoa, whoa, buddy, it's not about the 75 days and then be like, I made it, and then I'm going to go back to nothing, like, the nothingness.”

It's, how do I figure out consistently over the long haul to do the difficult things that actually matter in my life, that actually have meaning and actually make it difficult? And when you look on the time horizon, like, that is really the hard thing. The posting your workout to do in your diet for this constrained time, that is not the difficult thing.

We can all kind of force our way to make it through it, but it's not about forcing your way to make it through it. It's finding how to make it sustainable and part of who you are for the long haul.

Ted Ryce: Yeah. And I feel like, at least in my industry, that's not an easy sell, if that's what I sell, for lack of a better word. But when I see the people who are really crushing it financially, it's like, keto, fasting, just, the harder, the better, the strict, more strict, and yeah.

And then people wonder why like, “Oh, well, I ended up gaining the weight back or…And then they'll say something like, “I just need to go back to that whole 30 where it works so well for me,” and then I'm like, “But if it works, so well, why are you still doing it? I don't understand.”

And it's just this on and off again. And what I ended up ended up realizing it's just the comfort zone for people. So, you talk a lot about this in your book. Your book’s awesome. I wasn't sure how it was going to go down when it first started listening.

And then what I hear the main theme—I'm not all the way done yet, because I really have been taking it in. I love these types of books that talk about this really philosophy, but it's about managing our stress is a big component. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Steve Magness: Absolutely. Because here's what I think: stress tends to do a couple different things is it tends to narrow us. And it tends to focus us on the danger, or the thing that is stressing us out. And it tends to also push us towards safety, comfort and etc.

So, a lot of managing your stress in this regard is like, how do you approach it in the right way, and then get comfortable with understanding what that stress is, so that you can like sit with it and then experience it, instead of seeing it as like, again, this enemy that I often need to push away.

Because we're all going to experience stress in our lives. There's no escaping it. But we can either have a negative experience out of it or a positive experience. And I think, you know, going back to the hard 30/75 and all that stuff is, what often happens is we can manage that stress over a combined period of time, right? It's like…

Ted Ryce: Not that hard, or it’s easier, let's say.

Steve Magness: Right. You know, it's easier to do that, because we know where the finish line is. But in life, there's one finish line, I guess. And it's when we're dead. But it's a very long race—to use another analogy.

And I think when we have those confined periods, there's two things that happen with handling stress, and if we look at motivation as well, is often those challenges. Let me use this as an example. They do two things, they allow us to see that we can make progress, they allow us to have this finish line—actually three.

And those two things together can like stoke our motivation. But they're often from what I'd call an external end, meaning the outcome is the motivation. But the outcome, at some point, is going to become more difficult and difficult to experience and accomplish, which is why diets often fail. We can stay in them while we're maybe losing our weights and our bodies looking different. But that's only a very constrained period of time for most of us.

And then we're going to get to this kind of steady state, you know, defined zone, and we're going to lose that external motivator, because we're not changing, we're not seeing progress. And that's why if you look at the psychology and research for handling stressful events, or stressful moments, the internal motivators are much better.

And the analogy or comparison I'd use here is, those external motivators are essentially like lighter fluid. They look great. They have a big flame, but it burns out really quickly. Unless there's something else to kindle in there. What we want are those long lasting, not as fun to look at, like slow burning coals, essentially. That's what that internal motivation is that will keep us going through the long haul.

So many things are coming up for me while you're talking. I just want to say this in case anybody… I think the idea with the diet, it's very easy to connect with for people listening to this show, because it’s one of our main focuses. But even thinking about relationships, that honeymoon period where it's like, everything's great, you're having sex all the time, everything's just fantastic.

And then it's like, you start to realize it's more of a… It's like an ongoing process, right? There needs to be some maintenance. And it takes work to do that. And what I would ask you: for any type of situation or new job, or starting… I remember when I started my podcast, I was, oh my god, the first year was amazing.

And then it turned into like—I still love doing these. But it turned into this, oh, my gosh, the honeymoon wears off. You're like, “I’ve got to make this make money, so it can be self-sustaining.” And so what have you learned about how to keep things going when that lighter fluid wears off? How do you keep the candle going?

Steve Magness: Yeah, that's a great question. I think that's something that we all struggle with. But if you look at, again, the psychology and research, it kind of simplifies it to a couple of different things is, A, you want to do or pursue the activity, mostly, from a point of what I call like a mastery mindset. Meaning, yes, you want it to succeed, yes, you want to make the money, etc, because that allows you to do it.

But you're doing it almost dislike that craftsman trying to master the craft. Again, not all the time. But let's say at least 51% of the time where it's like, I'm pursuing this thing, because it challenges me, and helps me grow and live and adapt in a positive manner. So that's number one.

The other thing that is really important to developing that long lasting motivation is what we call autonomy, which is essentially feeling like you can make an impact, like you have a sense of control over what you're doing. And not that it's just kind of from the outside being dictated and demanding.

And this is actually where a lot of burnout in the workplace comes from, is people feel like they're micromanaged, and have no sense of autonomy, meaning they don't feel like they can impact anything in a positive direction. So they essentially default to, “Well, what's the point” mode. Like, “Why try?”

And we often blame them like, “Oh, your motivation is not there.” But it's their environment that is creating this constricting and controlling place that kind of holds them down. And then the last two things that are really important for this long-lasting motivation, are a sense of belonging.

So, do you feel connected to the work to others in your community? Like it's more than just you alone out there doing this and trudging through this? And if you feel that sense of belonging and connection, you're going to have that more positive motivation?

And then the last part, which I'll just kind of combine into purpose and meaning, is the thing meaningful? Does it provide direction in your life? Does it have some purpose that, again, is not just to make some dollars, which can be part of it, but more so, that it brings something positive to your life, then it's driven by something that is important.

And often, people ask, “Well, how do I find this?” To me, it's going back to why you started the thing, because often our meaning and purpose was like, really high at that point when we got interested in it, because we didn't know that we could make money at this or what have you, is really going back to the point of like, well, why did I get into this?

What was the purpose behind it and the meaning behind it? And does that still hold? And if it does, reminding yourself of that can go a long way for enhancing that motivation?

Ted Ryce: Yeah, very interesting. Another thing that comes to mind from some of the experiences…so I coach, mostly entrepreneurs or other very busy professionals with that loss, and you'll see, this something I've had to work very hard with my clients about.

And you'll see, they'll come in, like you said, high motivation, full lighter fluid, lose 10 pounds, maybe even 15. They feel good. And then that goes away. And so what I hear you saying is, if a person's in that situation, you really got to get dialled into the things that you just mentioned.

And the thing that stood out to me the most is like, why are you doing this? What is the purpose that this serves? And reconnecting with that? Did I understand correctly?

Steve Magness: Exactly. Purpose is like a performance enhancer. I'm going to take you to the athletic world, because there's some fascinating research and science in this area, where it essentially shows that you know, if you have a purpose that is greater than yourself, and by greater than yourself, I just mean that it's like, “Oh, I'm just doing this to make some money,” or whatever have you, what happens is you're actually able to push further.

So, they've tested these ideas in the exercise science world where like, they'll essentially shock the muscle to see if it still has juice in it, essentially energy in it. And you can see how far people can push to complete or close to complete exhaustion.

And people will push further if, for example, they're running this race, because they're raising funds for cancer research or something that has some meaning behind it, or they're part of a team where it's like other people are depending on them and it's more than them just out there alone.

And I think the same thing applies when we take it out of exercise to other aspects of our life, is that purpose can provide that guiding Northstar to remind you of, well, why you're going through the difficult moments. And this is actually one of the best things you can do, is when you're in that moment, where you're thinking, “Oh, I've got to quit,” or what have you, is create space for that perspective to remind you why you chose to do this.

Because if you chose to do this, then your brain almost gets that special kick where it's like, “Oh, yes, I'm not trapped. I'm not a prisoner being tortured here. I chose to do this. Well, why did I choose to do this? Because for whatever reason, this is the journey I wanted to take and explore.”

And that will, again, give a little bit more of that motivation and boost, so that you can handle the really difficult thing. And one other thing that I'd say here that is kind of connected to this, as well, as I mentioned, like that being part of a team, is again, there's some fascinating psychology that shows when we're with other people, or supported by other people, the difficult seems more manageable.

And there was this fascinating study where they took people and they essentially put them in an FMRI brain scanning machine to look at their brain. And there were spouses, and it was when, let's say the wife alone in the machine, what they would do is they didn't or do something stressful, like they put a snake in a small cage right next to the head of the person to make them scared and freak out.

And you could see it in their brain, their brain’s fear center would go through the roof. When they took the spouse of the person and put them like next to the person in the machine. So that wife and husband were standing, or the husband was standing next to her and holding their hand often, the fear response center doesn't go as high.

It's just like a little blip. Why? Because when we feel supported and connected, we interpret that stress differently. We say, “Okay, by myself, this might be overwhelming, but it's okay, I have others around me who can support me.” And the same thing occurs similarly, just briefly, when they took people, same thing, wife, spouse, teammate all this stuff, and gave them a really heavy box to lift.

When you're alone, you guessed that that box weighs, I don't know, 200 pounds, when your husband is standing next to you or your partner standing next to you, you guessed the box is 150 pounds, and you literally judge it as easier to lift, and your husband or wife or spouse isn't helping you. They're just standing there.

And I think that sends such an important message, which is if we want to tackle difficult things, like have that community have that connection, have that support, because that will literally change how you see the stress that you're experiencing.

Ted Ryce: So powerful, and wow, brings up so many things. There's also another study where like, a baby monkey had a fake mother and was able to like…Are you familiar with that study?

Steve Magness: Yes.

Ted Ryce: My business partner showed it to me recently. Could you give that example? Could you talk about it?

Steve Magness: Yeah, exactly. So, there was a study—and I think this is the one you're referring to. There's been a lot of them. Essentially, what happens is researchers found that with monkeys, like the mom or being there, was so important for the connection and belonging.

And when they took that away, they would literally have these fake kind of puppet moms, essentially. And that would be the replacer for the connection where it created that sense of security. And they would bond to this thing just to have something to bond to and then be able to a handle stressful experience.

And what's really interesting is in human research, this has actually long been studied, and it's called—I believe it's Attachment Theory, which essentially says that when we form a secure attachment with people around us, we feel less stressed, we’re more likely to take calculated risks when we feel what's called an insecure attachment.

Which is, we don't know if we're going to have that support, we don't know if we're supported, we don't know if we're going to be punished, we kind of shy away, we experience the stress more so, we don't take risks, and this applies readily in the workplace and office place, especially for leaders, where if you think about it as: what kind of environment are you creating?

If you create an entirely fear based environment, you're actually making your workers less resilient and less tough because they're going to be responding in this insecure attachment place. Well, if you create an environment that has what we often call: psychological safety, which is essentially, “I feel secure enough to take calculated positive risks and that I'll be supported in doing so.” We feel more comfortable taking on difficult projects and we're more creative.

Ted Ryce: This is so powerful because just like in business where there's a lot of strategies you can implement that are successful or in health where you can implement a lot of different strategies, people can't implement them effectively when there's too much stress in their life, is what I've seen. And so half what I do with my clients when it's that type of situation is what you might call coaching on stress reduction.

And then it's so funny to watch sometimes where even a client recently was telling me, “Oh, are you sure that there's not something wrong with my insulin levels or hormone or...?” He just gave a complicated physiological reason for maybe why he was struggling, and I was like, “This is all stress related, don't believe me, let's just use this as a hypothesis, test some things to reduce your stress and then see what happens.”

And then you saw the scale started dropping again, right? And he was able to—what happens with stress too, we don't take risks, we think we're on top of things, but our memory isn't so good because we're so focused. Like you said, stress is great for focusing you, right? But it's not so good for helping your short-term memory or any of the other executive functions.

Impulse control, you're thinking, “Well, I got to get this proposal done. Oh gosh, I'm really stressed out and let's reach for a glass of scotch or some food and just keep going out.” And so, what I'm trying to get out here is just, people—I'll say it like this, Steve, one of my mentors in business said, “Listen Ted, you talk about stress, people don't even realize there's a connection there.”

And for me being healthy or managing health, it's all about stress management. How we deal with stress, what ways we deal with it, and I don't think people get that. Do you see people understanding this or is your book like the first time that people are hearing about how stress might be more than just something in their head, and idea in their head?

Steve Magness: No, that's a great question, and I think it is, I think what you and I and others are trying to do is, change the conversation on that. Where it is often, I think people—let me step back, when you think of stress and you think of like, “Oh, this is just in my head,” it often tells people is like, “Oh, I should just tough through this,” or just like, “it's only stress,” when they don't see the actual physical and psychological ramifications that come from this and through this.

And I think that's what I'm trying to get at in this book a lot—is that we need to understand and appreciate. Like you said, “The stress that can occur,” and then figure out, “Okay, is this something that I can decrease and deal with or alleviate?” Or is this something that often is like, “Okay, I can't eliminate this stress, so how do I navigate this in a productive and positive manner?” And that's where that conversation I think needs to head and go more.

Ted Ryce: And if you're listening right now, you really want to get this book. I'm thinking about making my clients or at least some of my clients for whom it's especially relevant to read it because people in general, just have these beliefs about stress or that it's not that important, it's just about what you do. And then when things don't work out, it's this complicated—like in the fat loss example I gave, it's like maybe something's wrong with my metabolism, which there's nothing wrong.

So, the book is called, Do Hard Things: Why We Get Resilience Wrong and the Surprising Science of Real Toughness. And you can find that on Amazon. I'm an audiobook guy, so I've been listening to it during my walks. That helped me with my stress, by the way, it's one of my favorite things to combine, is walking on the treadmill at a low intensity or walking outside, listening to an audio book.

And this has been such a great book to listen to because it talks about the real challenges that we're facing and we're not acknowledging, and we also have some mistaken beliefs and that's what I want to kind of shift to, because you use a lot of examples of fake toughness. Can you talk about why we get resilience wrong and what fake toughness is?

Steve Magness: Yeah, absolutely. So, I think similar to what we just talked about stress is that: toughness, often, we have these wrong ideas. We have this idea that it's the external often, it's the bravado and talking a big game and posting, as we talked about earlier, like the crazy workout we did on Instagram, or what have you?

But a lot of that is, it's the cheap stuff, that's talk. What really matters is what's inside in this internal strength or inner strength to be able to tackle and do the difficult thing over the long haul. And to me, that is different than what I'd call, “The Fake Stuff Is”. So, a lot of this book is like, “Okay, if we realize and recognize what fake toughness is then what is inner strength.”

Then to me, it's being able to, you know, if I was to simplify it, it's feeling any sort of discomfort, anxiety, or stress, and then creating the space to navigate it, instead of just saying, “Hey, I'm just going to try and bulldoze my way through and grip my teeth and get on the other side of this.” And you see this all the time in sport, right?

It's athletics where they tell you, “Hey, no pain, no gain,” it's when they say, “Ignore your emotions and feelings, like forget all that stuff, just bulldoze ahead,” it's when we do crazy exercises for no point, except for punishment instead of exercises to get better at what we're trying to get better at.

So, to me again, it's like, how do we redefine this toughness to do what we all want to do? Which is handling difficult moments and challenges in a productive way that leads to growth.

Ted Ryce: There's sometimes where we need to compartmentalize and for example, I was sitting in the dentist chair the other day, getting my tooth drill because I chipped it eating some oysters, there was some shell and something. So, I had to sit there and white knuckle it through the process. Thankfully, it was only 20 minutes, and it wasn't so like—it was just extremely uncomfortable.

Or a more extreme example might be, you know, someone in battle, maybe that's not—in a gunfight, you don't want to stop and talk about the feelings that are coming up for you because you're in a gunfight, right? But most of the time and most of us, don't find ourselves in those extreme situations but we have that sort of reaction to it.

And I don't know what the cultural history is of toughness, but I assume some of it at least comes from the World War II times and the…Right? Like I'm in martial arts and a lot of the martial arts training which I got so frustrated with because it's like, “Hey, we're going to beat this shit out of you, if you survive, you're going to be a black belt and you'll be…” and it's like, “Wait a minute, my joints hurt, I don't even see myself making it.”

And I have the—psychologically I'm tough enough, but there's something wrong with this process, and then I started realizing a lot of this martial arts training comes from the way they prep people to go to war. And maybe that's important, maybe you don't care about your knee when the world is on the line, but if that's not the case, we need a better approach.

Steve Magness: Exactly, I'm glad you brought that up and so much—if you look at the history, so much of our ideals are come from the military. And often what we did is: we took the wrong lessons from them because often the crazy things they did to “Be tough.”

Well, A, is often, they occur when they're like initially sorting people, meaning like, “Hey, can you handle and make it in the military or not? Because we want to make sure that you can make it.” So, it's not a development exercise and if you looked at how often—especially in the US now, how we develop some of these skills in the military, it's completely different than throwing people into the—you know, against the wall and seeing if they break or not.

And the other part is, again, often, these ideas come from older military. So, it's like, World War II. Well, why were people just trying to do diff…you know, throwing against the wall? Well, it's because we have this draft, we need people, we got to train them up really quickly because we're in the middle of this war that literally could be the end of the world.

That isn't the reality for most of us. What we're more concerned about is, how do we develop these skills and these abilities? So, for example, in martial arts, it's not, “Hey, I want to find the one or two people who can make the black belt.” In the real world, it's, I want to make sure that everybody can improve and develop to reach their potential.

Whether that's a black belt to brown belt, yellow belt, whatever their ends sealing is. I don't just want a couple of the eggs to survive when I throw them against the wall. And I think when we reframe toughness as the skill that we can develop in that, “Hey, I don't know where your in capacity is, but here are the tools to do so to get better at it,” then we're in a much better frame of mind than if we just say, “Hey, the strongest survive, and forget about all the rest of you.”

And what actually happens is: we lose some really good people. So maybe to tell a story from the book is: there's a famous football coach named Paul Bear Bryant, who was famous for his coaching at Alabama but before he was out of Alabama, he was at Texas A&M, and he put these athletes through this training camp from hell.

Which was essentially like, “I'm going to make you do crazy difficult things in the heat, no water, all that good old school stuff,” this was the 1950s “and whoever survives you're going to be tough and we're going to win.” And the story, the legend goes like, he did this and then they became a great team.

What the legend often leaves out is that, that year they only won one game. They sucked; they were horrible after it. It wasn't until a couple years later where they got good, mostly because they got better players. Only like, seven or so players were left on the team that went through the really hard camp that they then didn't do afterwards.

But the other interesting part of this story that I think was fascinating is, we often have this view of, “Oh, the people who don't make it, who don't survive, they're weak.”

Ted Ryce: Right.

Steve Magness: But I went back, and I looked in this particular case and I looked well, “Who didn't survive?” There were guys who went on to play in the NFL, who quit, there were guys who changed sports, who became baseball stars for Texas A&M who quit, there was literally a war hero who went on and became this ace spider pilot and then commander in the Navy who didn't survive the camp.

So, it's not that they were weak, it's that they probably said, “You know what? This sucks and isn't utilizing my talent in the best way, I'm going to go find another area where I can utilize this talent without being miserable.” And I think that's often what happens in the workplace too, is we think like, “Oh, I'm going to be a jerk and toughen these people up.”

Well, if they're talented, they're going to be like, “Well, why am I suffering through this? I'm going to go find something that allows me to thrive,” and you've just lost someone talented who could have helped your company or organization.

Ted Ryce: I remember a client that I worked with, who was having some trouble. I got along with the guy, but he had a 600 person billion-dollar company. And the way he talk about his employees, it was like, “Man, what's going on?” You could tell he led by an iron fist.

And I remember him getting really frustrated because he was losing some key people, one of them left to Facebook, and it's like, he tried to keep him by paying him more money, but the guy wanted out and it was because of the environment.

And Steve, I remember that part from your book and it's a really important part, and some of us—people think they're doing the right thing by being tough and the intention may be good but the reality is: you have to look at maybe your approach needs to be upgraded and maybe even the doing the hard thing would be to take that hard look at yourself and your approach and be honest about it instead of just kind of going with that comfortable narrative. Like, “Hey, if they're really tough, they'll survive, they'll...”

Steve Magness: Exactly.

Ted Ryce: [Inaudible 35:18]

Steve Magness: No, I think you're spot on because this is often—the hardest thing is actually, dealing with our own bias and getting out of our own way, which often we get in our own way by sitting there and being like, “Okay, you know it's their fault, my employee's fault they left, or I'm not going to evaluate how I lead or the environment that I create,” because that would mean like, “Oh, maybe I'm not doing everything perfect or what have you.”

So often that hard thing is that introspection, is can you take the time to look at the items that you're doing and seeing if that is leading you down the path in the right direction.

And I also, you know, I'd be remiss if I didn't comment on that story you told of the person that lost someone to Facebook. Well, what did they do? They tried to throw more money at them, and that is often the solution that we use, and we think, “Oh, I'm going to throw money at them, and this will solve everything.”

But often that's the easy path, why? Because it's money and it hurts the company maybe a little bit, but there's nothing you have to change, you're essentially saying, “Hey, here's some money.” And what it does do is it doesn't look at the problems underneath. Why is this person choosing to leave this company? Who presumably has already enough money to live a pretty good life because they're in this field and all this good stuff.

Why are they choosing to do that? Maybe it's because the money—yes, it matters to a degree, but the underlying motivators and the supportive environment and the environment where someone feels like, “Yeah, they can be challenged, but they're challenged in a way that allows them to grow as in both in the job and as a person is more important.”

So, to me, if you're leading an organization is, how do you create that environment that allows people, yeah, you're going to take on difficult challenges, yeah, you're going to do crazy hard work, but you're doing it in a way that is supportive instead of this threatening and controlling, which again, threatening and controlling often puts us in—to use this word analogy—it puts us in a place where we start playing not to lose, instead of playing to win and we want people to be able to play to win.

Ted Ryce: And that's what I love about the whole theme here. This isn't about let's all be nicer and more kind. I mean, sure, that's important but to put the morality aside or however you want to talk about it, this is about getting better results.

And I want to return to your story about the military, because one of the things you talk about in the book, it's like, we have this story about what the military does to make their people super tough, but that's not actually what they're doing. Can you talk about the types of training that the military is using now to develop elite warriors to elite soldiers?

Steve Magness: Absolutely, and I think this applies because I think what we have, as you said, there is—-and as I talked about in the book is that, we have this image of the military, it's like the 1940s military, where they go do crazy things, we put them through hell and then they survive and that's how we train them.

That is not how the military develops this resilience and this toughness, if you look at it, is very strategic. The military is actually the nation's largest employer of sports psychologists, why? Because they want to do things correctly and work on this mental game. How do they do that? Well, first they teach before they train.

So, they teach their soldiers the skills in which they need to know, to navigate the extreme situations they're going to deal with. So, in most cases, depending on the branch, they literally have a 400-page book on the mental and psychological skills which can be everything from the mindset you take, to what to focus on, where to shift your attention under a very stressful environment, to how to deal with and withstand maybe being captured and tortured?

Like all of those mental strategies are in there to give people the tools. And then what they do is, they don't just say, “Okay, you read a book, we showed you some PowerPoints, we taught you some things, go do it, or good luck.” They just put them in situations where we're like, “Okay, we're going to train you up.

So, we're going to put you through simulated, maybe survival training or simulated training where you're out there with the team in the woods and just kind of on your own and you got to figure things out or even simulated again, like, prisoner war situations. And they go through, and they have their team looking and evaluating as you go through this, how will people experience it?

And often, it's really difficult, it feels real. But that's what they're going to encounter in the real world, if they are in those situations. And then after—so you go through this situation, they call it Essentially Stress Inoculation, where you're experiencing stress and then you get used to and adjust to it.

And then afterwards, the most important part is they review it. Where did you go wrong? What can we approve on? Where were your mental and psychological skills lacking a little bit? So, it creates this environment for growth and development.

And the other thing I'd say on this military, which I found fascinating is- early on when they just kind of start this process, the number of military soldiers, elite operators who experience what psychologists call Disassociation, which is essentially when your mind kind of freaks out, and you're in this kind of crazy fog of war, state and stress. Something like 96% of soldiers experience that the first time they get in that situation.

So, it's not like they're innately good at this and have this talent, what happens is: the military says, “Okay, you're human, like none of us are super soldiers, we’ve all got to experience this, now let's work so that you can navigate this and we're going to teach you, give you the tools, put you through difficult things, but also review and evaluate so that you can learn and adapt and grow.”

Ted Ryce: If you want to perform like a superhuman, you need to recognize the limitations of being human first and work on those.

Steve Magness: Exactly, and I think that's something that we often get wrong is- we think like, “Oh, the best of the best,” like they're just gifted and superhuman,” and it's like, “No! they have to come to terms with it.”

And actually, I was talking with someone who went into the special forces, and they put it very clearly, they said, “You know, often, you think the people who are going to make it are the ones who are like, “Oh yeah, on outside, like, I'm really tough, this is easy, I got this.”

Those are the people who fail because when push comes to shove, it's the people who can kind of see it clear eyed and say, “I'm not superhuman, I might be capable, and I might be really good at what I'm doing, but like, this is going to be tough, I need to see it clearly.”

Those are the people who make it through the challenging times. So, I think that lesson applies to us as well as whenever we're put through challenges, can we see it clearly and rationally so that we know what we're facing.

Ted Ryce: I love the talk about the military because what you’ve got to love about the military regardless on where you sit politically or whatever, is that: the stakes are extremely high, we're talking about life or death for real. If a business even goes out of business—I mean, there's so many businesses, you go out of business, you start another one, does it suck? I mean, it must, but the stakes are lower.

And so, people don't step up and do what they need to do, and I think that's why the using the military as an example, or a model, rather, of like, “Okay, well, what do you do to be super successful?” These guys they're employing sports psychologists, as per your example, they're realizing, “Hey, listen, we're talking about competing on a world stage, we don't know what's going to happen.”

I've traveled a lot, all over the world, lived in many different countries. I'm in Brazil right now, I mean, the military is aware of all these crazy things that are happening, and you can't afford to be lost in a narrative that leads to poor results because the risk is quite large. And I think that's a lesson everyone can take away from your examples of the military.

Steve, one thing I would ask you is: what are some things that we can do to be more elite? I'm not going to go to BUD/S and do some BUD/S training just to develop mental toughness. What are some things I can do or someone listening can do, or maybe some of the things that you've done to create more resilience?

Steve Magness: So, I think the great thing about this and the research back this up as well, is that: small moments in your life, train this mental muscle, because I really look at it as a mental muscle, which is, when we take on challenges, we can either have that alarm going off, telling us to escape, quit, etc.

Or we can train to turn that alarm down low enough so that we can navigate and make the good wise decision. And to me, and again, the research and the psychology all show us, which is small moments matter. So even something as simple as adopting a mindfulness practice can train that alarm, why? Because well, think about it.

What is mindfulness besides sitting there with your thoughts and training to sit with them and accept, instead of reacting and shift your attention to every thought that comes into your head. And people often think, “Oh, I don't want to meditate, whatever.”

Well, that's fine, again, the research shows that even a couple minutes a day of just sitting with your thoughts, can have a profound impact on this. Other things that I think are important is having something in your life that challenges you a little bit in some way.

Now in my life, that regularly is often exercise, and I'm not like going to the well and exercise, but it's something where it's like, I'm going to get out the door and do something that is a little bit difficult that puts me in an uncomfortable situation, which can train this mental muscle.

So, what I would say is, “Look for the spaces of the simple things where your mind tends to go to, like escape, worry alarm going off, and instead of seeing those as like, “Oh no, this is a bad thing,” I would see this as, “Oh, this is opportunity to train this mental muscle” and try just to sit with it or go towards it. So again, you can essentially tell your brain, or your brain learns like, “Hey, I'm okay, I don't need to freak out, I can navigate this, it's going to be alright.”

Ted Ryce: I have a friend who wrote a book, Hunting Discomfort, and it's much less—he goes into the science, not quite as much as you do in your book, Do Hard Things, but he very much says like, “Hey, hunt discomfort, those things that you feel that are difficult, go towards them.”

Another friend in past guest, Chris Friesen, who's a neuropsychologist, but he does performance coaching. He was talking about the Law of Contrasting, and I don't remember all the details that he talked about in the episode about this law, but what he was basically saying is, “If you do want to experience less anxiety in your life, you have to train yourself up.”

Because if you don't, you get to a point where let's say you're doing very well financially, and you're redoing the floor in your big five-bedroom house, and they brought sandstone instead of moonstone and you freak out.

And so, if you find yourself in that place, it's really important to start to pay attention to this and dive into books like Steve's, where it's going to start to help shift that narrative.

Steve, I know we're coming up on time here, but based on the research that you've done, how has that changed some of the things that you approach in your life, doing hard things? Can you share a story?

Steve Magness: Yeah, absolutely. So, I think for me, one of the things that has really kind of changed or shifted my mindset actually is, how I lead and impact others. And the reason this changed is pretty simple, is in the book I was doing some research, and found this fascinating work by a bunch of psychologists that looked at coaching in the NBA.

So, the highest level, right? And they found that when players played for a coach who they classified as authoritarian, or almost abusive, the yeller, screamer, like “I'm going to punish you if you mess it up.”

Ted Ryce: Like the guy who grabbed people's throats,

Steve Magness: Exactly.

Ted Ryce: I forget the guy's name,

Steve Magness: Bobby Knight, yep.

Ted Ryce: Bobby Knight, broke record.

Steve Magness: When people played for those people like that, what happened is: their performance declined, they performed worse. And in NBA, their levels of aggressive fouls, like technical fouls, where they couldn't control their emotion and they just let it all out, those went up. But what was interesting, and I think the reason it changed my perspective is: those changes that worse performance and more aggression lasted for the rest of the athlete's career, even when they were under another coach.

Ted Ryce: Wow.

Steve Magness: So, to me, as someone who works in this space or anyone who is leading, that almost humbles me to a degree and says, “You know what, I better take the time to get this right.”

And I'm not going to be perfect, but to lead in a productive manner, that allows people to hopefully thrive, even when they're gone from here, because you have that lasting impact. And that to me is, again, it's a powerful responsibility but it's also a powerful message to send as well.

Ted Ryce: Wow, that is something to think about, that arguably traumatic experience with a bad coach ingrains those habits, and I do believe they can be broken, but it doesn't just happen, they don't just get a better coach and then it magically goes away, it sticks with them.

It also brings up kids that act out as well for me, thinking about that as a kid who acted out against some, you know, I love my parents, but they had some very different old school, say, approaches.

Steve, it's been such a great conversation, I feel like I could go another hour, there's so many things that I even personally, I would love to ask you and, but I think we'll save it for part two, if you'd be willing to come back on.

Steve Magness: That sounds great, Ted. I've really enjoyed this conversation, it's been fun to have.

Ted Ryce: Yeah, me too, Steve. And if you're enjoying this conversation as well, and you'd like to perhaps do something hard and challenge yourself to change the narrative, or at least investigate the narrative that you have about what's truly hard? And what's not?

And maybe how you can be like the military and do things better by using data and experience, get Steve's book, Do Hard Things. It's available on Amazon and they have the audio book available, kindle hardcover, all the versions. I'm listening to the audio book. I really enjoy the narrator that you chose.

So, that's always important for audiobooks. And if you want to read more about—or go to Steve's website and maybe read more about what he's up to, speaking, the podcast, etc. Go to The Growth EQ, so www.thegrowtheq.com anywhere else you want people to go, Steve?

Steve Magness: No, you can find my work everywhere. I'm on social media @SteveMagnness, so appreciate it, and appreciate this conversation as well. As I said, I had a lot of fun and you're bringing a lot of value to your listener. So, I love the pod.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.